Planting the Edgy Bits of Giant Marsh

A recent winter visit to the Point Pinole shoreline near Richmond felt like a step outside of time. I was there to watch a small team implement the next phase of a big scientific idea, but the area’s typical fog had rolled in thick, and the entire endeavor was cloaked in a fairy mist.

Ducks paddled and dabbled in a dark flock, colors and feathers indistinct. Dogs walked their masked masters on a high trail. Dried stalks of purple teasel — coneheads freed of seeds by the bracing Bay breeze — lay felled across the slopes: in preparation for a restoration planting spree, East Bay Parks had cleared that prickly invader. Freight trains blasted and planes rumbled somewhere out of sight. Hidden by the high tide and low fog, oysters clung to human-made reefs offshore.

The mist messed with my sense of place. But I had been here before, to the Living Shoreline project at Giant Marsh. Now, I was back to see the latest phase of a multi-year, multi-habitat restoration up close and personal. On this day, they were not building oyster reefs or planting eelgrass out in the shallows, as they had in 2019. Instead they had moved shoreward and upland, to plant what scientists call a “transition zone,” restoring native plants on some slumps and shelves of the bluffs. If — or when — the Bay should rise six feet, this would be the new waterfront.

“You try to allow for dynamic change when planting for a transition zone,” says project manager Marilyn Latta of the State Coastal Conservancy. “We are not attempting to put any plant into a fixed point forever. When we plan for planting shifting landscapes, we want to think about what species are already on site, what species are in a local, more pristine and intact, reference site, and what species might do well in the future.”

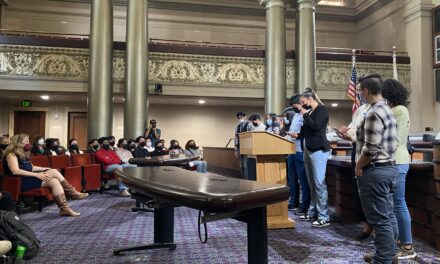

As I waited, a crew of four workers and two supervisors materialized from the mist. They began unloading diverse trays of plants and placing them next to marked plots, fluttering like a tiny carnival with color-coded flags — actually used to show where different species should go in the planting palette.

“A lot of what we’re doing here is designed for quick results,” says Jeanne Hammond, a project manager with Oakland consulting firm Olofson Environmental, who was supervising the work. “With all the urgency due to climate change and sea-level rise, we need to be getting marshes up to speed now. We need habitat to mature rapidly enough to function. That’s why we use container plants with developed roots [instead of seed]: it gets the project further along in the trajectory faster.”

The crew from San Diego-based RECON Environmental are all young guys — hoods up, masks on, gloved fingers and kneecaps sticky with wet soil. The ground was still damp from January rain, making digging small holes for the new plants easier. “I like being outside. I’ve worked with plants all my life and I just enjoy it,” says Adam Adair, the RECON crew leader.

As I watched, a dog trotted off-leash into the planting site and squatted to leave a deposit right in front of us. The owner arrived next, an older woman in an elegant purple jacket holding a utilitarian blue bag. The hues seemed too bright, out of place in the muted, almost black-and-white shades of the morning.

Olofson biologist Pim Laulikitnont-Lee was the only one of the crew wearing colors. Her safety-orange billcap and day-glow gloves moved like bright embers through the gloom. “We nestle our plots so we don’t disturb the native bunch grasses,” she says, adding that this site was a change of pace for her; she spends most of her days in places where she needs waders, not hiking boots.

Click to see enlarged slideshow.

Over two days of work, the crew planted 1,000 individuals from five native species into this site. When they were through, the transition zone was the new home to hopeful clusters of creeping wild rye, western ragweed, marsh baccharis, western goldenrod, and Pacific aster.

One month later the plants were doing well, but with little rain this winter, needed occasional watering. “Since we first started working in Bay marshes in the 1990s, the biggest change in our work has been watering due to prolonged drought,” says Hammond. “Back then, there was a chance we didn’t need to water. Now we must.”

Day Two with the Airboat

A week later, the planting crew was headed for deep Bay muck along two eroding edges of the salt marsh. The sky was cobalt, and still waters glinted with reflected sunlight. An energetic flock of willets foraged along the mudflat.

Across a stretch of Bay on the Richmond Rod and Gun Club pier, Hammond and a crew from a nationwide restoration company called SOLitude Lake Management moved trays of Pacific cordgrass from pickup trucks onto an airboat. A bystander who looked like a hunter asked Hammond what they were up to, and they got talking.

“I noticed there’s more green grass growing offshore under the water out there than there ever has been in 20 years or so I’ve been boating around here. Is that good or bad?” the man asked in a gruff voice.

“Good for ducks and fish,” Hammond said, going on to explain that the man was seeing eelgrass, a native plant that grows in the subtidal zone that it is great habitat for many living creatures in the Bay. “And you have the Bay’s biggest eelgrass bed right here by your club,” she added.

“Do you know who the biggest funders of habitat restoration are? Hunters and fishers, like me,” the man said as they parted.

“I sure do,” Hammond replied. “We couldn’t do it without you.”

In a great whir of air and water, the airboat soon set off for the work site, a small patch of eroding salt marsh near some of the most landward oyster reefs. The site had been pretreated with herbicide to remove invasive Atlantic cordgrass and its hybrids — part of a 20-year program to erase the invader from Bay marshes.

The new batch of Pacific cordgrass ready to be planted was grown in the nearby Watershed Nursery, in Richmond. Cordgrass replicates itself easily, spreading through underground roots. So if a team collects 100 stems of the native species for the nursery to grow, they will soon have 1,000 ready to set root in the Bay ooze; wild “parent” plants had only been collected three or four times in the last decade, according to Hammond.

That day’s task was an experiment, testing three different Pacific cordgrass planting methods. The first placed 20 small plants in a dense cluster, less than two feet on a side. In the second, a larger square of four “sod” pieces was nestled into the muck, instead of individual plants. And last, burlap bags containing clean, dense soil were each planted with two individual plants, and then placed directly into the marsh — an effort to reclaim area that has already become too eroded to plant directly.

Click to see enlarged slideshow.

Show Your Work and Scale Up

The January and February 2022 planting days I witnessed were just the latest steps in the Giant Marsh Living Shoreline Project. It all began in 2019, when four of the project’s habitat treatments (human-made oyster reefs and plantings of eelgrass, California seablite, and rockweed, a brown macroalgae) were installed off Point Pinole.

“This park is a special jewel, because of access to the shore, and access to untouched, undredged historic marsh,” says local ranger Brett Whitmer of East Bay Regional Parks. “This project will help it all become more resilient to sea-level rise.”

The Giant Marsh team continues to monitor the results of their efforts, and test different restoration methods, so such projects can gain ground all around the Bay. According to the Coastal Conservancy’s Marilyn Latta, a large team is now writing proposals to do ten similar-scale projects all at once, mostly in the central Bay. The goal is to create best practices as well as design and construction guidance that will facilitate a wide variety of projects in different locations.

“We just spent ten years working hard site-by-site, and if we don’t scale up over the next ten years, it’s a missed opportunity,” she says. “It’s time to apply all the knowledge so we can have continuity.”

Freelancer Jacoba Charles contributed to this story.

More

- Bi-Coastal Experiment with Oysters & Infrastructure (KneeDeep Times 2021)

- Moonrise over Giant Marsh: New Monitoring Data from Two-Year-Old Supershore Project (Estuary News Magazine 2021)

- Super-Shore: A Multi-Habitat Experiment at Giant Marsh (Estuary News 2019)

- Giant Marsh Living Shoreline (California Coastal Conservancy)

- Invasive Spartina Project

- Olofson Environmental

- RECON Environmental

- SOLitude Lake Management