Collecting and Unifying Regional Metrics on Wetland Health

The region’s wetlands, critical buffers for flood protection from sea level rise and storm surge, are at risk of drowning if they can’t migrate inland or build up in elevation. So how do we know if they’re healthy? Better monitoring.

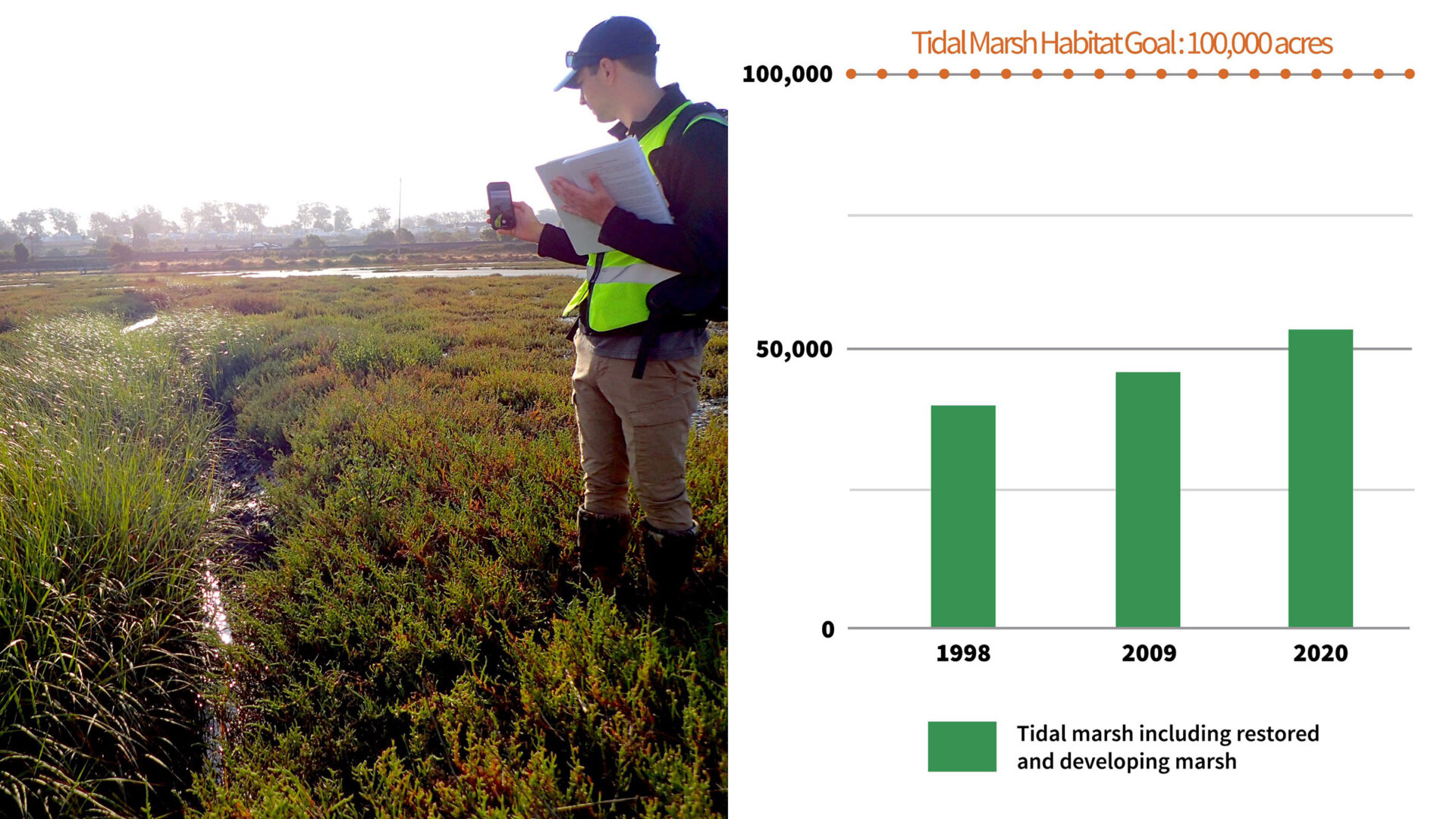

In 1999, regional managers vowed to restore 100,000 acres of tidal wetlands in the San Francisco Estuary by 2030. More than two decades later, over 53,000 acres have been or are in the process of being restored.

But the effort to track those acres, and monitor the success of tidal marsh restoration projects, has relied on a patchwork of data collection efforts, each using different sampling methods over different time scales. Managers are still often unclear on whether these wetlands are flourishing or providing good habitat for target fish, birds and mammals.

“We know very little about many of these habitats; they’ve just never been sampled in a standardized way,” says Levi Lewis, UC Davis fish ecologist.

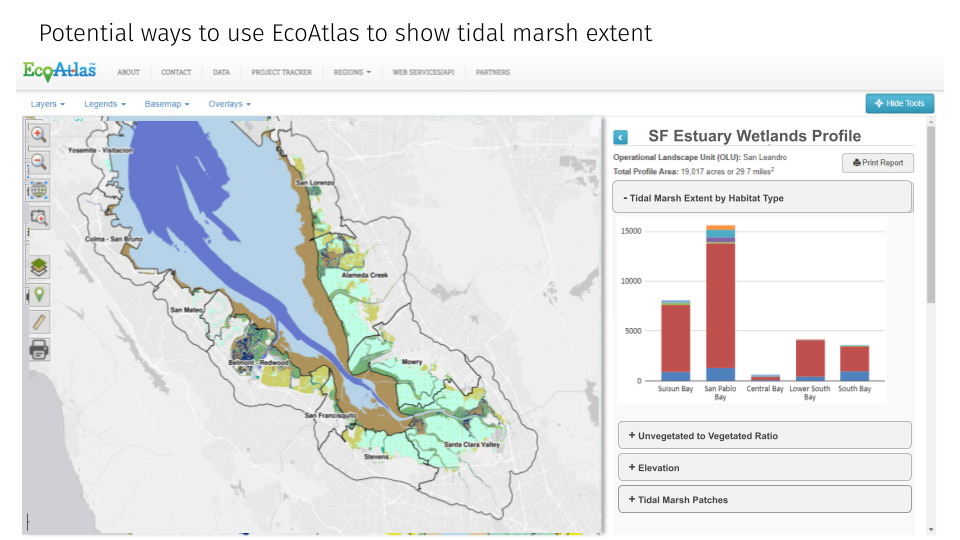

Six years in the making, an effort to close these gaps is finally gaining traction. Early in 2025, the Wetlands Regional Monitoring Program began to put more crews in the field, sensors in the ground, and links in the public access EcoAtlas map to regularly track changes in the Bay’s wetland ecology from Silicon Valley to Suisun Bay. The program will also link all this monitoring to similar efforts in the Delta, where about ⅓ of the estuary’s total wetlands can be found, and where nearly all the monitoring expertise and resources have been focused historically.

“It’s a collaborative regional monitoring program that aims to improve wetland restoration across the whole San Francisco Estuary,” says Aviva Rossi, a lead scientist with the WRMP.

SFEI’s Dave Peterson conducts monitoring in Dotson Marsh, one of the wetlands counted in SFEI’s most current assessment of wetland extent and restoration progress throughout the Bay. Data & Photo: SFEI

The project is co-managed by the San Francisco Estuary Institute and Estuary Partnership, and funded for the next two years via the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority and US EPA. The program will work to establish a regional dataset that can elevate estuarywide science and enable researchers and managers to compare how different wetlands are changing under the influence of restoration projects, as well as in response to sea level rise, drought, and other environmental shifts.

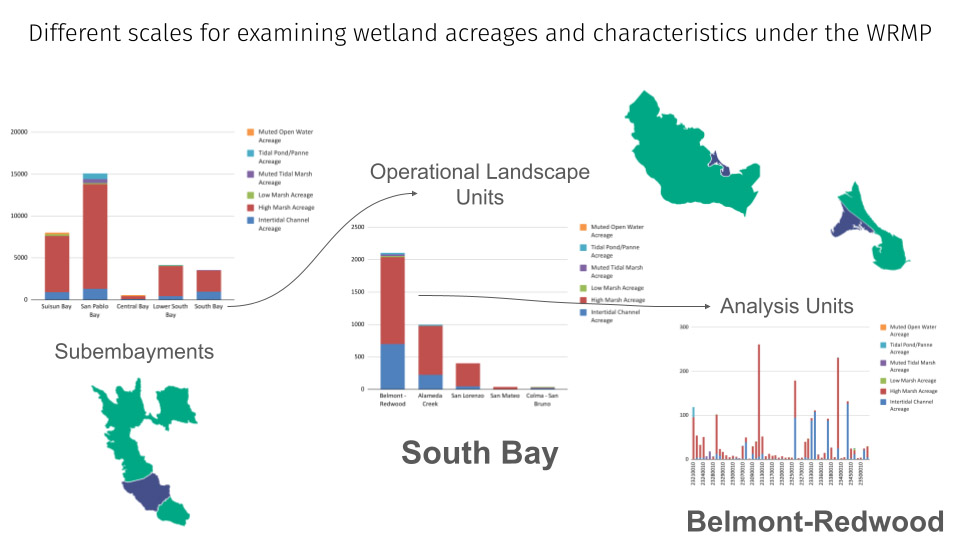

“The WRMP will standardize what is collected and how it’s collected so that you can get a more unified assessment of how these sites are changing over time,” says Lisa Beers, also a lead scientist with the WRMP. “[We’ll] know that any changes we see in the extent of wetlands over time are due to actual management actions and restorations, rather than differences in methodology or how the mapping was done.”

Eyes on the Marsh

The mosaic nature of estuary and especially wetland monitoring have made communicating between agencies and securing reliable sources of funding a major challenge for decades. Programs like the Interagency Ecological Program in the Delta, and the Regional Monitoring Program for contaminants in San Francisco Bay, have long sought to coordinate, share and optimize research and monitoring endeavors — but it isn’t easy.

“Since we don’t have any central governing agency that’s effective from the coastal ocean to the headwaters, you have to piecemeal this stuff together from existing programs across, in [our] case, nine agencies, and we don’t always get it right,” says Steve Culberson, lead scientist at the Interagency Ecological Program and program manager with the Delta Stewardship Council Delta science program.

Scientists from a Department of Water Resources integrated science team monitor fish in the Yolo Bypass, California in 2024. Photo: Andrew Nixon, DWR, 2024.

Combining existing surveys of the Delta — many focused on fish and water-quality sampling — with new monitoring of recently restored habitats has proven difficult. While fish and birds can move freely between project sites, information can’t.

Many existing monitoring programs are tied to specific management questions, or to specific restoration sites designed to mitigate impacts from a specific development or water diversion project. Often, that kind of monitoring can be patchy, project-centric, and short-lived, as most permits require just two to five years of sampling.

“The WRMP is different in that it’s regional and long-term,” says Rossi. “The scope and scale involves coordinating across a big area with multiple jurisdictions and players, as well as supporting project-based efforts and making them more efficient and less costly. That’s all really challenging to pull off, which is why it’s taken decades to get to this moment.”

The WRMP will collect samples in previously understudied areas in the South, North, and Suisun Bays, such as Eden Landing, Ravenswood, Galinas, Novato, and the Petaluma and Napa River systems. The same consistent, trackable, repeatable methods will be used to collect metrics across sites and regions, and over seasons and years. This January, for example, a field crew established some new long-term vegetation transects (a set line across the marsh where plant growth is measured), placed new piezometers in the ground (which measure groundwater rise), and re-instated some sediment accumulation sensors to better align with the stepped-up monitoring effort, among other efforts that will help pin down baseline conditions of wetlands.

Future sampling will collect data on a suite of metrics to judge the health and functioning of wetlands, including water quality metrics such as temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen. Habitat assessments will track vegetation cover, biodiversity, and fish species abundance as they change over time due to climate change, development, runoff, and sea level rise. Data collected as part of the project will be publicly available on an online data portal, as well as in published reports.

“People are excited, including landowners,” says Rossi. She points out that this coordination can actually reduce the number of people stomping around on sensitive (and sometimes privately-owned) landscapes.

Monitoring Will Optimize Investments in Climate Ready Landscapes

With climate change, the region’s wetlands are now not only critical buffers for flood protection from sea level rise and storm surge, but also at risk of drowning if they can’t migrate inland or build up in elevation. The WRMP can help the region better understand some of the nuances of how wetlands are responding.

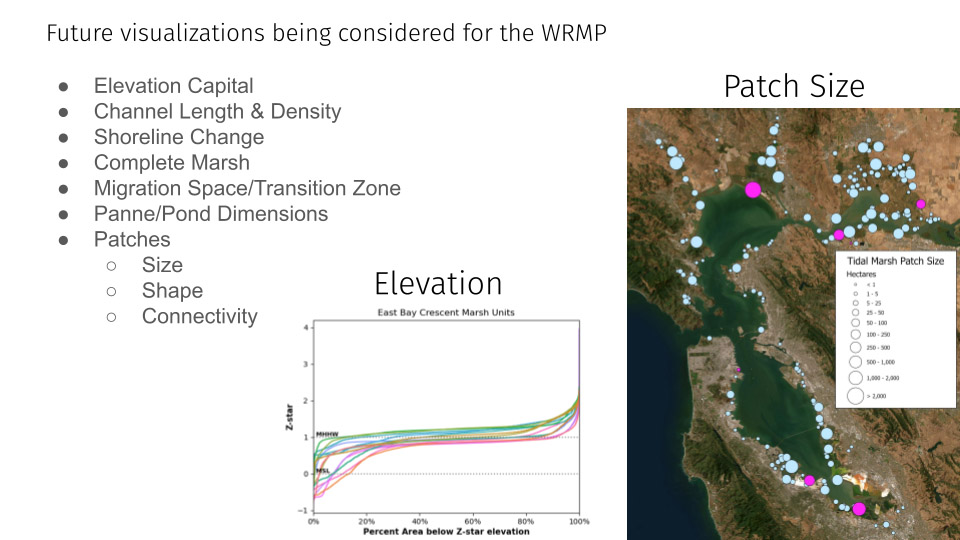

For the first time ever, for example, researchers will collect low tide elevation data (LIDAR) for the entire lower estuary all at once this year. The WRMP is also contracting with the US Geological Survey to monitor and install sediment elevation measuring devices in tidal wetlands all around the Bay.

“This data will help us determine if wetlands are gaining elevation over time or subsiding,” says Lisa Beers.

USGS scientist measures and profiles sediment behavior within Petaluma Marsh, including generating data for the WRMP. Photo: USGS

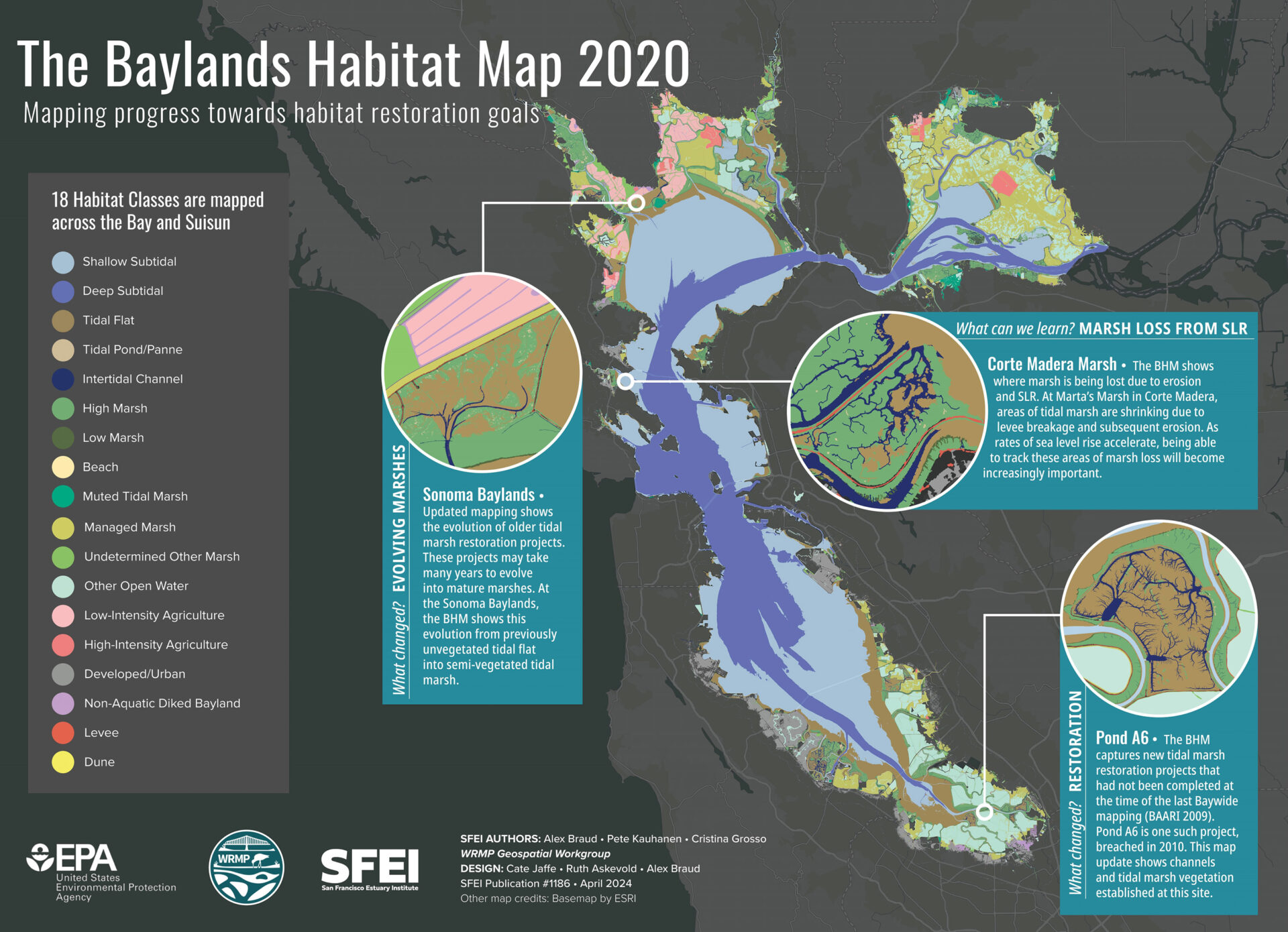

The WRMP team will also create a 2025 version of the Baylands Habitat Map to help keep track of the Estuary’s restoration goals.

“Resources are always going to be limited when you’re trying to build these big programs,” says Rossi. “We need to weave together a lot of different components to make sure that this region, that has such a wealth of scientists and regulators and projects, all of which have all been happening for a while, are working together so everybody’s efforts count for more.”

Ariel Rubissow Okamoto contributed to reporting for this story.

Top Photo: USGS scientists monitoring Petaluma Marsh. Photo: USGS