New Wildlife Bridges Help Critters Cross the Road

Mountain lions, salamanders, frogs, and humans will soon find new under and overpasses in collision hot spots on Santa Cruz, Santa Clara, and Alameda roads.

On the 101 Freeway near the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles, the world’s largest wildlife crossing is taking shape. The $92 million project, officially named the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, is part of a growing movement across California — including in the Bay Area — to reconnect critical habitat sliced asunder by roads.

For people, roads represent freedom, movement, a way to get from here to there. For wildlife, roads often mean death.

Death by road can be immediate if an animal gets struck by a zooming two-ton metal vehicle. These accidents are perilous for humans, too — and expensive. Based on a report analyzing tens of thousands of roadkill observations, the University of California, Davis’ Road Ecology Center determined that the San Francisco Bay Area has the highest costs from wildlife-vehicle collisions in California, averaging over $21.4 million a year.

Wildlife death can also be the slow result of habitat fragmentation. With their fast cars and steady din, roads often become impassable barriers for wildlife needing to move — whether they’re seeking food, water, territory, mates, or responding to increasingly frequent extreme weather events. Over time, the size and genetic diversity of populations hemmed in between human development drops, making them vulnerable to mutation and disease. Some of California’s most iconic species, like mountain lions (also called puma), tiger salamanders, and desert tortoises, are at serious risk.

Completed landbridge, another kind of wildlife crossing project, in Oklahoma. Photo: Susan Vineyard, I-Stock

Historically, the core tenet of biodiversity conservation was to protect large, contiguous, intact habitat areas with minimal disturbance and partitions. The result is that most of the Bay Area’s protected lands — which make up almost 30% of its area — are isolated and far from roads and communities.

“That’s fantastic for conserving biodiversity within that large patch,” says Bryan Largay, conservation director at the Land Trust of Santa Cruz County, “but really lousy for ensuring that patches are connected to one another and that people have access.” And roads aren’t the only impediment to animal movement. Many of the Bay Area’s big open spaces are separated by human development, from shopping malls to neighborhoods. That’s why linking fragmented landscapes is now a key conservation priority, Largay says.

Taking Stock of the Region’s Crossing Projects

A diverse array of wildlife crossing projects are in the works all around the Bay Area, although some may be hard to spot from a car.

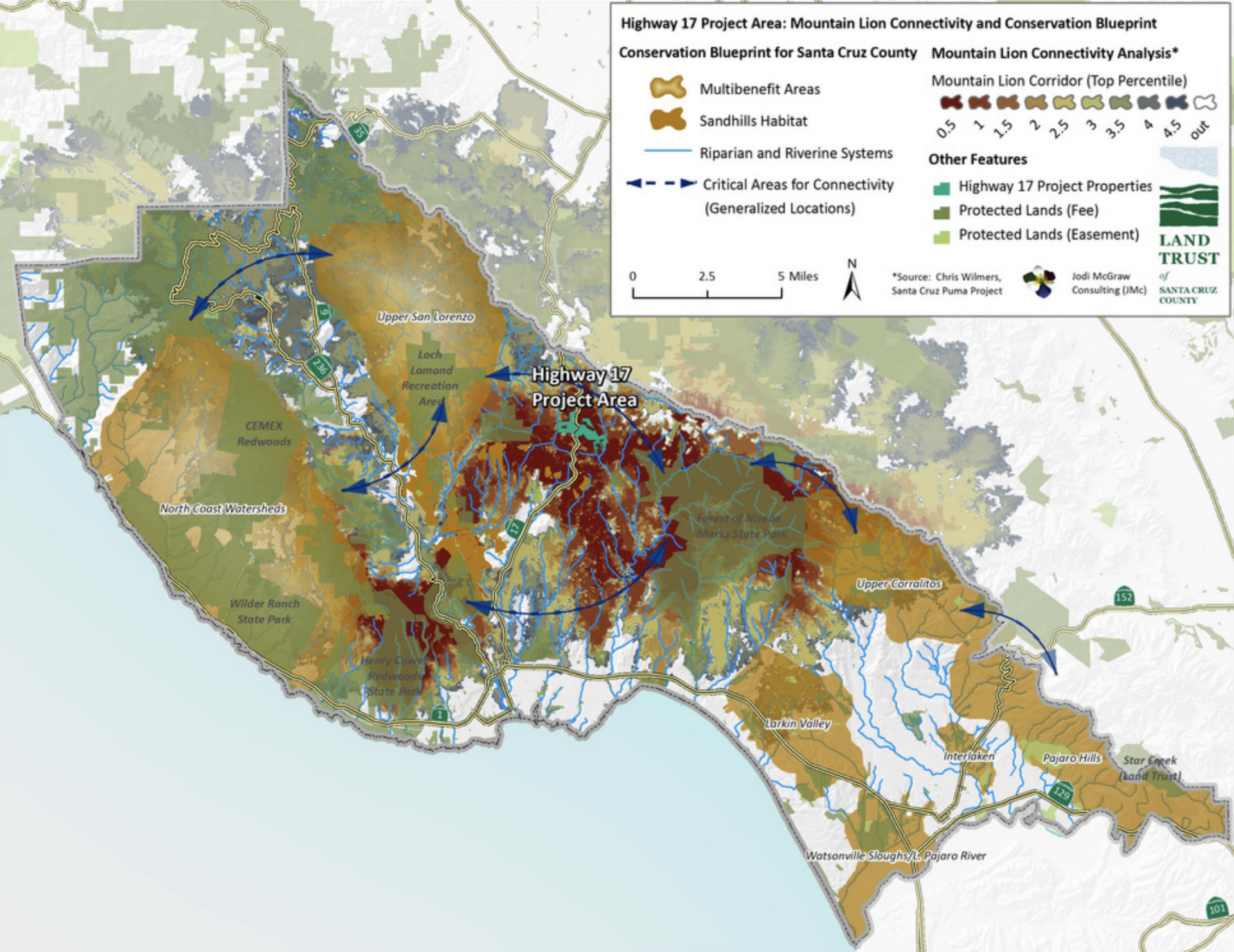

This past December, construction finished on the Highway 17 wildlife undercrossing at Laurel Curve to reconnect the northern and southern parts of the Santa Cruz Mountains. About half of all wildlife-vehicle collisions on Highway 17 occurred on this bendy section of the road. The interagency partnership responsible for Laurel Curve, which included the county land trust, CalTrans, and the Regional Transportation Commission, was so successful that it paved the way for SB790, passed in 2021, which created a mitigation credit framework through which CalTrans can fund projects across the state that support wildlife connectivity while enhancing public safety.

Mountain lion habitat and connectivity around the Laurel Curve Project. Map courtesy Land Trust of Santa Cruz County

The Laurel Curve project will soon be followed by a second crossing restoring wildlife movement between the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Gabilan Range further inland.

Mountain lions are a key beneficiary of these kinds of crossing projects. Large, solitary animals with vast territories, mountain lions need room to roam. As urbanization converts their habitats into islands, mountain lions have no choice but to mate with their kin. This inbreeding begets a loss of genetic diversity that, allowed to progress, leads to kinked tails, undescended testicles, and eventually extinction. Mountain lions with kinked tails have already been seen in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

But mountain lions aren’t the only local species that need help crossing the road. A species with long toes, rather than long legs, is set to benefit from a project planned for Highway 1. The Santa Cruz long-toed salamander is a federally endangered species with a known range of only 50 square miles, and Highway 1 runs right through the middle of it. Spending most of the summer buried in moist leaf litter, the salamanders eventually emerge and migrate over to breeding ponds. Though just four to five inches long, these salamanders will only move across large openings — like a road — because “they don’t like to feel like they’re going back underground,” Largay says. The new crossings will be designed with ample space for little amphibians, big cats, and even bigger elk.

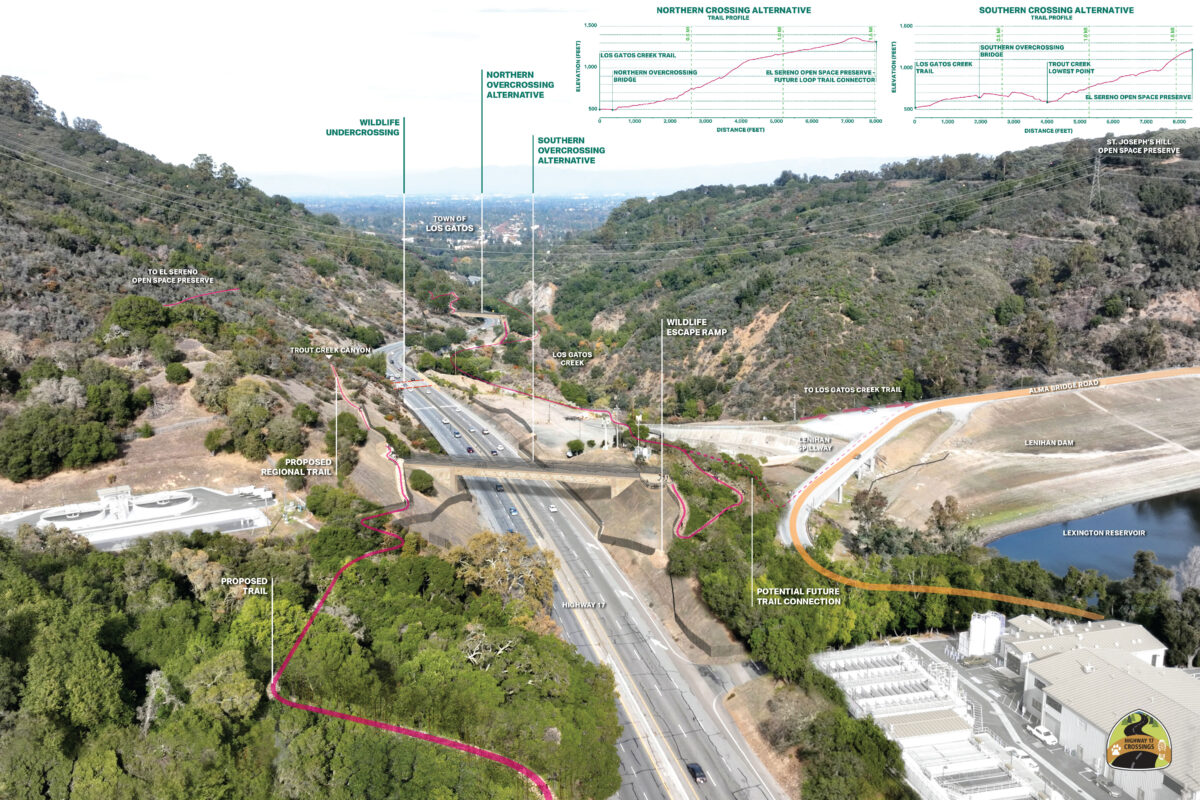

There is yet another species in pursuit of natural open space,one with ten toes and two legs: humans. The Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District, or “Midpen,” is working with CalTrans to develop wildlife and recreational trail crossings for Highway 17 that will link over 30,000 acres of protected lands and connect over 50 miles of existing trails, including the Bay Area Ridge Trail. While both humans and wildlife need to cross the road, the two species have different needs. The wildlife crossing will run beneath the highway, and the trail crossing over it.

Midpen’s planned project, complete with overcrossings for humans and undercrossings for wildlife. Images courtesy Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District

“Our mission has three prongs: protecting and preserving open space, restoring the health of the environment and its species, and providing opportunities for public recreation and non-intensive uses,” says Ryan McCauley, Midpen’s public affairs specialist. This project does all three, he adds.

Public support is crucial for landscape linkage projects, especially if they mean powerful cats will be roving nearby. Many people who live in mountain lion habitat have real concerns about safety, both their own and that of their pets and livestock. That’s why outreach and education is so important, McCauley says — not only to understand community members’ concerns, but also to share the message that “most of the Bay Area is prime habitat for mountain lions, so we want to make sure we’re respecting their space while also staying safe.” Coexistence is the goal, says McCauley, though it may be a long process of learning to live together.

Another deathtrap for wildlife is Alma Bridge Road in Santa Clara County, which encircles Lexington Reservoir, a manmade lake at the intersection of four open space preserves. A 2021 study found that of the nearly 14,000 adult newts that tried to traverse this road during their 2020-21 breeding season, almost 40% got squished by cars. Midpen’s Alma Bridge Road Newt Passage Project, slated for construction in 2027, aims to help. The proposed designs include elevating segments of the road and constructing undercrossings.

Alma Bridge Road. Photo: Emily Harwitz

Over in Alameda County, the East Bay Wildlife Crossings project is in its planning stages after receiving a $7 million grant from the Wildlife Conservation Board last year for planning and design. The proposed network of three over- or undercrossings will benefit large animals like mountain lions and tule elk, mid-sized animals like bobcats and badgers, and even smaller ones like the locally endangered California red-legged frog, California tiger salamander, and Alameda whipsnake. I-680, I-580, and SR-84 are all candidates for a new wildlife crossing.

This August, Governor Gavin Newsom visited many of the projects mentioned above as part of the Wildlife Crossings Across America tour that helped launch California Wildlife Reconnected, an initiative he spearheaded alongside state agencies and nonprofits, to leverage resources for habitat connectivity across the state. Wildlife crossings are a key part of California’s 30×30 commitment to conserve 30% of the state’s lands and coastal waters by 2030, the governor said in a press release. This year’s tour is specifically focused on California, and will cover over two dozen stops across 2,000 miles of the state.

More Than Four-legged Crossings

As global temperatures warm and climate change stresses ecosystems, scientists and conservation experts are calling for more careful planning of wildlife migration and escape routes, as well as caretaking by human neighbors. More needs to be done to consider how highway infrastructure, existing bridges, culverts, and private land could provide passage for not just wildlife, but also plants.

“As we think about climate change, we’re worried about increases in fire intensity and frequency, the introduction of non-native species, and increasing problems with disease, so fragmented populations are much more vulnerable,” says Esther Cole Adelsheim, an ecologist and conservation program manager at Stanford University.

Aquatic waterways are important, too. Many amphibians and fish depend on creeks that link ponds to each other, or connect the Bay to upland streams. When development cuts these waterways off, these creatures have no way to get to breeding grounds — or to cooler water, which will become increasingly critical to survival as temperatures warm.

Mountain lion. Photo: Warren A Metcalf, I-Stock

“One of the ways that species can adapt to climate change is by moving to suitable microclimates, so if they can’t move to a patch of habitat that works for them, they will not survive,” Adelsheim says. This includes plants, which have different ways of dispersing than the large mammals which have been the focus of many corridor studies. “I feel like plants, especially our natives, are perhaps more susceptible than is fully acknowledged,” she says.

Largay agrees. “This is where land stewardship by residents matters a lot,” he says, because sometimes plants or animals need to move across what is now a person’s “private property.” Individual community members can have a big impact on the survival of local species and ecosystems by transforming their properties from movement bottlenecks to corridors.

Largay views proximity to private property as a benefit: “There’s a really cool opportunity for people to understand what the native ecosystems are closest to where they live and how they might make their lands more permeable to pollinators, plants, and the bigger animals.”

At a time when people are more detached from nature than ever, perhaps reconnecting our landscapes can help us reconnect with the natural world around us.