Optimizing the Health Benefits of Urban Greens

The same features in urban parks that support biodiversity can also benefit human health. Even biodiversity itself may help us — and the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) wants to see more of it. To that end, the nonprofit released an innovative report in September called Ecology for Health. It’s a practical guide for planners and designers to aid both biodiversity and human health in urban settings.

Research into the link between nature and human health goes back decades. But scientists continue to learn more about which aspects of parks and other green spaces in cities — such as recreational amenities, shade, views, or plants and animal life — are most associated with different mental and physical health outcomes in humans, says SFEI environmental analyst Jennifer Symonds. One of seven co-authors of the report, Symonds also led an exhaustive review of the existing literature.

A conclusion that’s become increasingly clear (and that inspired SFEI to produce the guide in the first place, Symonds says) is that plant, animal, fungal, and human life can be intertwined to a fascinating extent, even in urban settings.

Two recent studies suggest that greater bird diversity is tied to better human well-being. And a 2007 study showed a positive association between overall plant diversity and human psychological well-being: the more of one, the more of the other. Plant species richness also has been linked to human microbiota biodiversity, Symonds says. “That is linked to improved human health, including reduced skin disease,” among other benefits.

Research has also shown that urban forests can (take a deep breath) improve mood, mental health, immune function, and BMI, and lower the prevalence of lung cancer, asthma, heat-related mortality, and preterm birth. Native flowering plants, meanwhile, may help reduce allergen sensitivity.

All of these can be deliberately designed into city parks and open spaces for maximum benefit, and that’s the main message behind SFEI’s new report.

Some features, however, might have to go. Artificial lighting is known to affect wildlife communication, orientation, reproduction timing, predation, habitat selection, and more. In humans, it’s “linked to increased breast and prostate cancer risk, increased cortisol, increased vector borne disease risk, and disruptions to circadian rhythm and melatonin production,” a chapter in the report on lighting reads. To reduce these impacts, the authors recommend limiting outdoor light intensity and “trespass,” also called light pollution, and avoiding blue-white light.

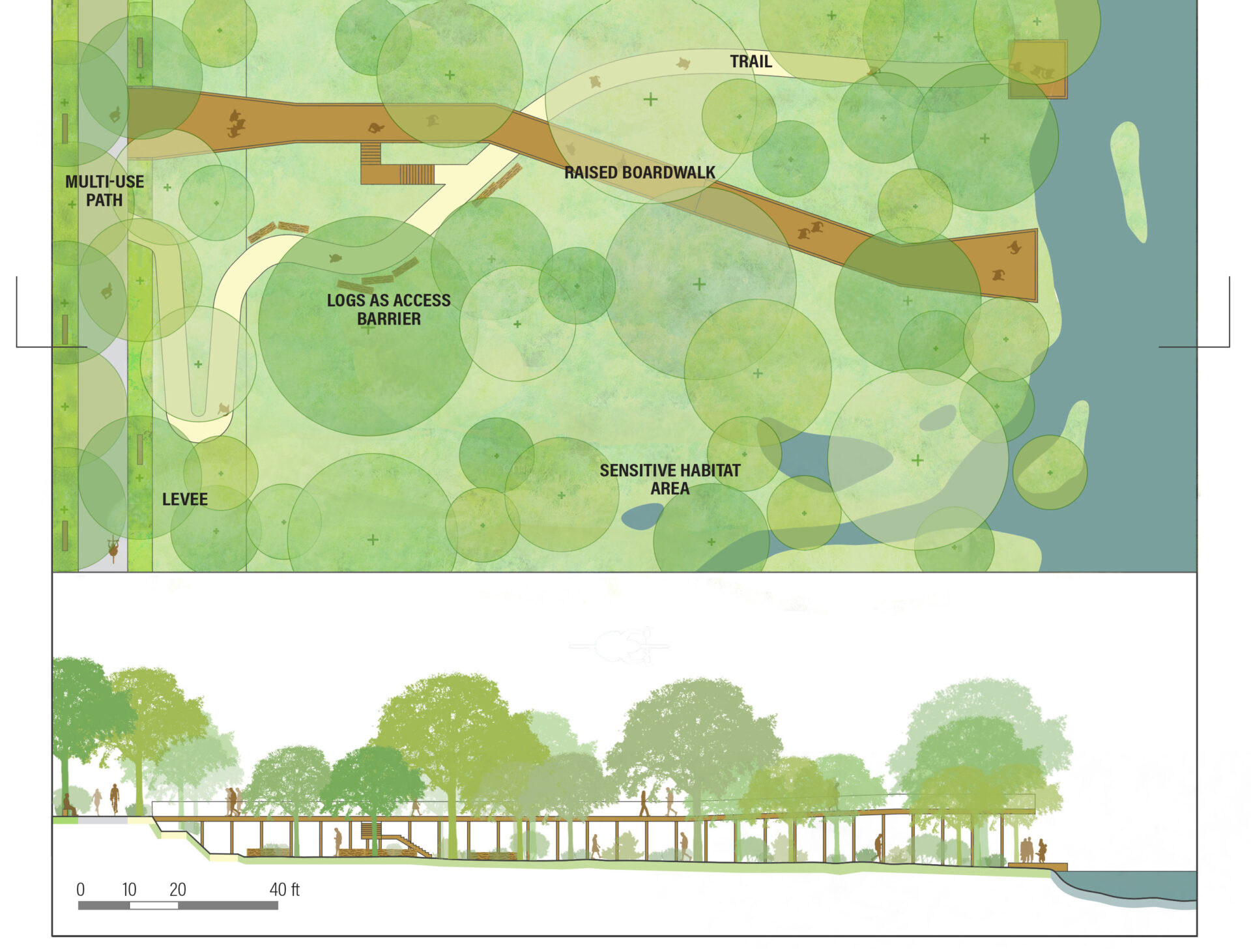

Other chapters in the report offer practical guidance on water features, grass alternatives, garden spaces, habitat complexity, and public access. And alongside direct impacts on health, the authors also explore co-benefits for things like shade and cooling, climate mitigation and adaptation, and flood and stormwater management — a suite of benefits sometimes referred to as “ecosystem services.”

Of course there are challenges. In some cases, the needs of people and nature conflict. Recreational access can disturb wildlife. Habitat complexity may reduce human access or perceived safety. And green spaces may take land away from other valuable uses like affordable housing.

The guide tackles these, too, with practical insights throughout. “We are excited to present this design guidance showing synergies and also addressing the tradeoffs between biodiversity and human health in urban spaces,” says co-author Karen Verpeet, SFEI’s Resilient Landscapes Program managing director.

SFEI’s goal now is to get eyes on Ecology For Health. In September, the organization gathered more than 50 local planners, designers, landscape architects, and other experts to review and discuss the report. “We’ve already gotten some really good feedback,” Symonds says.

Other Recent Posts

Boxes of Mud Could Tell a Hopeful Sediment Story

Scientists are testing whether dredged sediment placed in nearby shallows can help our wetlands keep pace with rising seas. Tiny tracers may reveal the answer.

“I Invite Everyone To Be a Scientist”

Plant tissue culture can help endangered species adapt to climate change. Amateur plant biologist Jasmine Neal’s community lab could make this tech more accessible.

How To Explain Extreme Weather Without the Fear Factor

Fear-based messaging about extreme weather can backfire. Here are some simple metaphors to explain climate change.

Live Near a Tiny Library? Join Our Citizen Marketing Campaign

KneeDeep asks readers to place paper zines in tiny street libraries to help us reach new folks.

Join KneeDeep Times for Lightning Talks with 8 Local Reporters at SF Climate Week

Lightning Talks with 8 Reporters for SF Climate Week

ReaderBoard

Once a month we share reader announcements: jobs, events, reports, and more.

Staying Wise About Fire – 5 Years Post-CZU

As insurance companies pull out and wildfire seasons intensify, Santa Cruz County residents navigate the complexities of staying fire-ready.

Artist Christa Grenawalt Paints with Rain

Snippet of insight from the artist about her work.

High-Concept Plans for a High-Risk Shoreline

OneShoreline’s effort to shield the Millbrae-Burlingame shoreline from flooding has to balance cost, habitat, and airport safety.

In a Climate Disaster, Your Car Won’t Save You

Fleeing wildfires without a car might seem scary, but so is being trapped in evacuation gridlock — and the hellscape of car-dependency.