Nested Plans Neck and Neck with Rising Bay

Like Russian dolls, Bay Area preparations for sea level rise finally began fitting together this fall.

In September, state legislators passed SB 272 (introduced by Senator John Laird), requiring coastal jurisdictions to make plans for the inevitable advance of the ocean. In October, Bay Area shoreline planners held their first public workshop on the development of a regional adaptation plan to minimize flooding. And in the same month, one of the region’s most impacted counties, San Mateo, went so far as to float the idea of an offshore barrier with operable doors — showing the way for other counties not as far along in planning for Bay creep.

“The state legislation is a game changer is some ways, but not in others,” says Dana Brechwald, Assistant Planning Director for Climate Adaptation with the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), which has been laying the groundwork via vulnerability assessments, flood mapping, and adaptation planning around the Bay for more than ten years. “Before we were trying to get this done on the basis of collaboration, engagement, and goodwill; now it is legislatively mandated.”

Within the region, San Mateo faces such daunting flood threats to both its coasts — San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean — that it’s been more pro-active than other counties in planning. The proposal for the offshore barrier is just the latest in a series of that started with the creation of a countywide special district in 2020 (OneShoreline). By 2023, the new flood resiliency district had produced guidance for cities along the Bay to protect against sea level rise, atmospheric rivers, and groundwater rise.

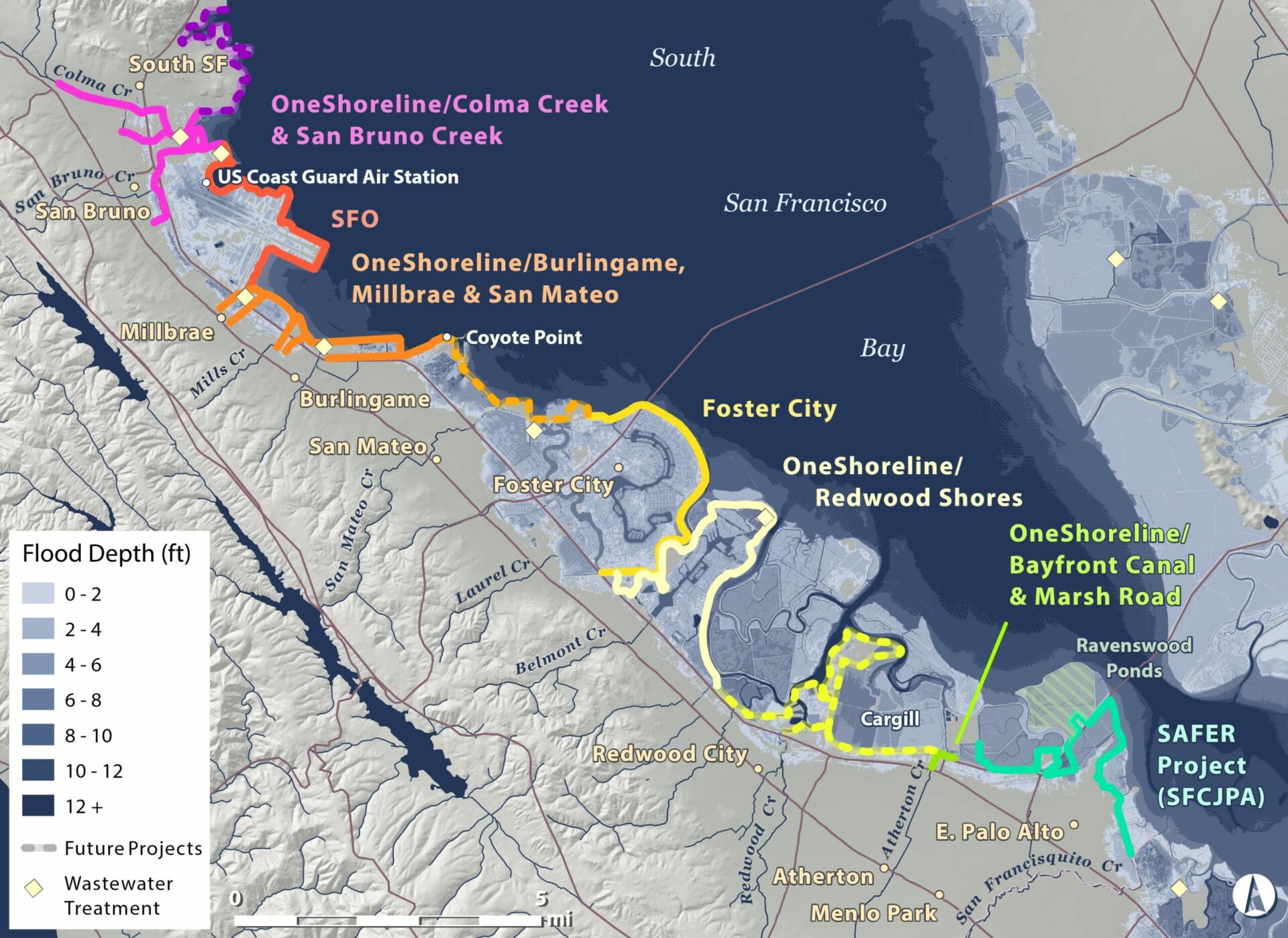

Map of flood and sea level rise resiliency planning areas along the San Mateo County shore, first published in KneeDeep in 2022. Map: Amber Manfree.

San Mateo County’s proposed offshore flood barrier would consist of both grey and green infrastructure and extend south from San Francisco International Airport (which is building its own sea level rise protection project) along Millbrae, Burlingame, and potentially as far as Coyote Point in the City of San Mateo. During extreme storms and tides the barrier doors would be closed to keep the tide out and create space for storm runoff from the five creeks that drain the area. Outside of these extreme high water events, OneShoreline or local cities would keep the doors open to allow for normal tidal action and watershed drainage important to shoreline habitats. As sea levels rise in the coming years, the doors could be closed more frequently or for longer periods.

“The structure hasn’t been designed yet, but it would likely be a thin barrier with habitat on one or both sides and many doors that we control, so not a levee to minimize the footprint and not one big gate that opens and closes,” explains One Shoreline’s executive officer Len Materman. “And if BCDC wants a trail on it, we would consider that.”

This type of barrier is just one of many alternatives OneShoreline’s team is looking at but the idea isn’t new — the US Fish & Wildlife Service has used similar structures to enhance wildlife habitat and recreation at different scales in both the South Bay and Delta.

“OneShoreline was created to address huge problems that need huge solutions. I don’t want our legacy to do things on the margins. I want to address this issue,” the Materman commented in an October 21 San Mateo Daily Journal article.

If SB272 is the biggest Russian doll and San Mateo’s One Shoreline plan the littlest, the nesting doll in the middle will be the Bay Area’s forthcoming regional adaptation plan — perhaps the farthest along in all these endeavors due to BCDC’s foresight. The regional agency recognized early that no city or county or community could become fully flood resilient on its own, and has been working to build local consensus about what to do via a joint platform called Bay Adapt.

“If we don’t act aggressively now, sea level rise will literally drown and overwhelm us,” says BCDC’s chair Zack Wasserman.

Even before passage of SB272, BCDC was stepping up work on the Bay Area’s regional adaptation plan, hiring consultants (Mithun) to research and review the literature (more than 90 documents so far) as a foundation. BCDC is now completing an online public opinion survey (last call November 3), and will be holding more regional and community-based workshops over the next 6-8 months.

Draft topics for a regional adaptation vision, now being surveyed and workshopped by BCDC. Art: Mithun

Next, BCDC will develop guidelines for subregional plans so all jurisdictions are on the same page, and impacts aren’t just exported to neighbors. The regional guidelines, to be completed by December 2024, will mirror requirements of SB 272, and become part of an overall Bay Area shoreline adaptation plan that also aggregates local plans and maps planned projects.

“We need to think about what a subregional plan should actually look like, and what scale they tackle?” says BCDC’s Brechwald. One challenge will be to create universally useful guidelines for a varied shore. While the North Bay, for example, might expand wetland restoration to soak up more water, there is little room to do that on the Oakland or San Francisco waterfronts. BCDC will also consider regulatory requirements for the new plans. “Will they have to go through CEQA or not, and how will they be made to align with other plans?” says Brechwald. “We have lots of questions to answer.”

Meanwhile, the passage of SB 272, which requires sub-regional plans to be completed by January 2034, led to a flurry of inquiries from communities worried about where their existing or evolving plans would fit in the new process, says Brechwald. She expects existing plans, such as those already completed for Alameda and San Mateo, could possibly be updated as part of a regular review cycle, rather than becoming misaligned with the guidelines coming out next year. “Nobody’s plans are going to be out of compliance right away,” she says.

MORE

Crunching the Adaptation Numbers, June 2023, KneeDeep

Big Plans for Big Problems, Nov 2021, KneeDeep

Resilience Hub, A quick glance Bay Area resources

State Fact Sheets on Legislative Change

Other Recent Posts

Boxes of Mud Could Tell a Hopeful Sediment Story

Scientists are testing whether dredged sediment placed in nearby shallows can help our wetlands keep pace with rising seas. Tiny tracers may reveal the answer.

“I Invite Everyone To Be a Scientist”

Plant tissue culture can help endangered species adapt to climate change. Amateur plant biologist Jasmine Neal’s community lab could make this tech more accessible.

How To Explain Extreme Weather Without the Fear Factor

Fear-based messaging about extreme weather can backfire. Here are some simple metaphors to explain climate change.

Live Near a Tiny Library? Join Our Citizen Marketing Campaign

KneeDeep asks readers to place paper zines in tiny street libraries to help us reach new folks.

Join KneeDeep Times for Lightning Talks with 8 Local Reporters at SF Climate Week

Lightning Talks with 8 Reporters for SF Climate Week

ReaderBoard

Once a month we share reader announcements: jobs, events, reports, and more.

Staying Wise About Fire – 5 Years Post-CZU

As insurance companies pull out and wildfire seasons intensify, Santa Cruz County residents navigate the complexities of staying fire-ready.

Artist Christa Grenawalt Paints with Rain

Snippet of insight from the artist about her work.

High-Concept Plans for a High-Risk Shoreline

OneShoreline’s effort to shield the Millbrae-Burlingame shoreline from flooding has to balance cost, habitat, and airport safety.

In a Climate Disaster, Your Car Won’t Save You

Fleeing wildfires without a car might seem scary, but so is being trapped in evacuation gridlock — and the hellscape of car-dependency.