Stoked for Car-Lite, Bike-Safe Living

“The biking itself is not the problem, it’s worrying about getting hit. But that can be fixed by street engineering.”

Four years ago, after I totaled our electric Nissan Leaf (no one was hurt!), my husband Steve Price made a radical proposal: What if we don’t replace the car? What if we buy electric bikes instead?

We decided that car-lite living would only work if we never deprived ourselves because we didn’t own a car. Since then we’ve been happily using a variety of modes of transportation as fits the need: e-bikes for errands around El Cerrito where we live; walks to the library, grocery store, and restaurants; AC Transit and BART for trips to Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco; Lyft and AAA’s GIG CarShare for car-dependent local outings; and car rentals and transit for getting out of town.

The author and her husband.

In El Cerrito, a small city north of Berkeley with a population of 26,000, transportation accounts for more than half of greenhouse-gas emissions, according to the city’s Climate Action and Adaptation Plan. Despite the growing alarm about climate change, the total amount of our emissions related to transportation has been increasing since 2015. If communities truly want to address their own greenhouse-gas emissions, figuring out how to get more people out of their cars is an urgent undertaking.

“Owning a two-ton vehicle should not be the cost of entry for running local errands and accessing services close to home,” my husband says to anyone who will listen. “It’s an unjust, inequitable tax on too many people.”

Transportation is largest source of greenhouse gasses

Two years ago, Steve and I helped co-found El Cerrito Strollers & Rollers, which advocates for safer multimodal streets in our town. We’re latecomers to the game: Across the Bay Area, local and regional bike activists have been advocating for better bike infrastructure for decades, not only because they want safer streets but also, more recently, because they want to be part of the solution for climate change.

“The transportation sector creates more carbon dioxide emissions in our communities than any other category, even as cars have become much cleaner over the years,” says Robert Prinz, advocacy director for Bike East Bay, which collaborates with several dozen bike advocacy groups and clubs, and regional transit organizations in the East Bay.

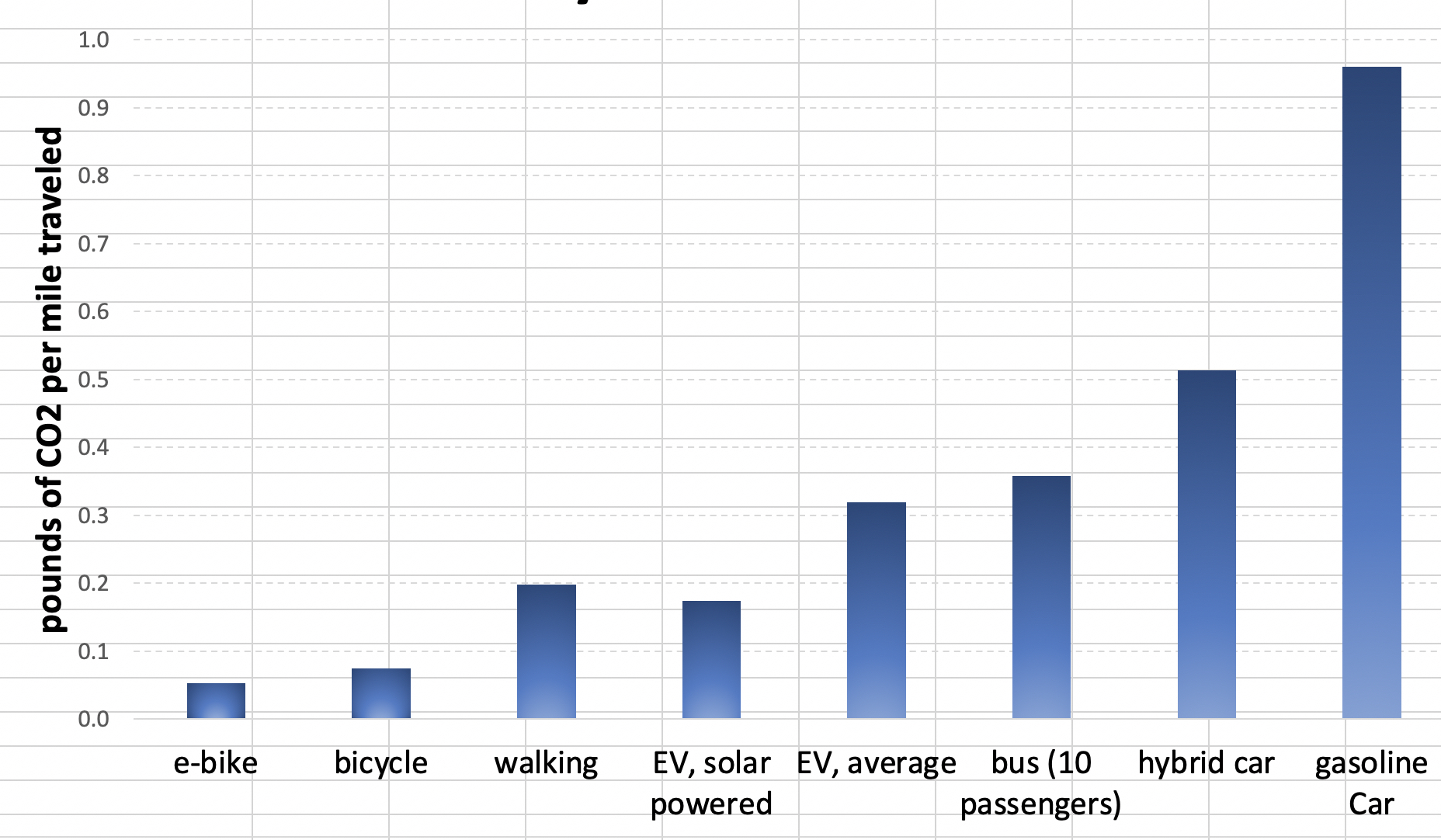

Total lifecycle carbon emissions for different transportation modes. Source: Seb Stott/Bike Radar.

By some estimates, the amount of carbon dioxide produced per mile by different transportation modes ranges from up to one pound of CO2 for gasoline-powered cars and around a third of a pound of CO2 for electric cars — but only a twentieth of a pound CO2 per mile for electric and road bikes, respectively. Walking, counterintuitively, has a slightly higher carbon impact than biking because it requires more calories and therefore more carbon emissions from food.

“If you want to reduce carbon emissions in transportation, it’s hard to do better than biking. So if we’re serious about reducing emissions, we need to make biking palatable to a lot of people ASAP,” says Andreas Kadavanich of Bike Fremont, which advocates for safe bicycling in Fremont, Union City, and Newark in the southern East Bay.

Safer streets for all

Bike advocates say that feeling and being safe while riding is the number one barrier to biking. In addition to cycling education, the best — and perhaps the only — way to get people onto bikes is through improvements to street infrastructure. The tools include physical traffic-calming on narrower, neighborhood streets; bike lanes painted on the street or protected and separate from car traffic with physical barriers or space between cars and bikes; and bike parking, giving cyclists someplace to secure bikes at their destinations.

Evidence is mounting that improving bicycling infrastructure translates into safer streets not just for cyclists but for walkers and drivers too. A 2019 analysis of road fatalities in the Journal of Transport & Health from 12 large U.S. cities over a 13-year period found that “higher intersection density, which typically corresponds to more compact and lower-speed built environments, was strongly associated with better road safety outcomes for all users.”

Cargo bikes parked in Albany. Photo: Amy Smolens.

“Protected and separated bike lanes made the biggest difference for safety by far, with 44% fewer deaths on the roads for all users,” Prinz says, who has seen similar results related to over 60 individual protected bikeway installations in the East Bay. Even if people never get on a bike, he says, they need them to know they are still getting benefits from the infrastructure.

Miles and miles of bike lanes in Fremont

El Cerrito isn’t the only East Bay city innovating its perks for pedal power. Further south, Fremont offers about 88 square miles of flatlands. “Geographically we’re perfect for bike riding,” says Kadavanich, 53, an engineer who commutes by bike from Fremont to San Jose. “It’s hard to get anywhere by walking, but most places are within biking distance, if it’s safe to bike there.”

The Bike Fremont booth at Niles Canyon Stroll & Roll in 2023. Photo: Bike Fremont.

In 2015 Fremont adopted Vision Zero — setting the goal of no traffic fatalities in the city — and in 2018 it launched an ambitious bicycle master plan. Fremont public works director Hans Larsen says the city currently has 34 miles of protected bike lanes, which include raised cycle tracks and lanes buffered by plastic bollards, concrete curbs, or parked cars, and 14 protected intersections. More of each are scheduled for completion over the next two years.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, traffic-related deaths averaged three per 100,000 people in Fremont in 2022, compared with 4.5 deaths in San Francisco, eight in Oakland, and 12 per 100,000 people nationally.

Bike parking is easy in Albany

In Albany — a mile-square city of about 20,000 people sandwiched between Berkeley, El Cerrito, and the San Francisco Bay — one of the areas bike advocates have focused on is providing bike parking in places people want and need to go, including along the busy Solano Avenue and San Pablo Avenue retail corridors and at local schools and parks.

Since 2012, in partnership with local businesses and the City of Albany, Albany Strollers & Rollers has installed 74 “bike bike racks:” distinctive, colorful racks in the shape of bicycles, at an average cost of $650 each. The cost is shared by the group and local businesses, and the city takes care of installation.

“By promoting bike parking at local businesses, we’re providing opportunities for residents to shop local while reducing vehicle miles traveled,” says Amy Smolens, 64, a TV sports producer. “The bike racks make it clear that cyclists are welcome as customers and clients. Maybe the person who drove today will see the racks and say, ‘Tomorrow I’m going to ride to my dentist appointment.’”

Kate Taylor of Albany’s Flora & Ferment Ciderhouse places an informational sticker on a new bike rack. Photo: Amy Smolens.

Biking for a better world

I don’t miss having to park and take care of a car, and I don’t suffer from FOMO. It’s been heartening to see our community rally around safer streets and to personally contribute in ways other than cutting down on single-use plastics and taking shorter showers.

Bike Fremont offers free bike repair workshops. Photo: Bike Fremont.

The motto of El Cerrito Strollers & Rollers is “Low-carbon access to the fruits of the city.” We now have about 300 people on our mailing list, and we’re stoked by the new enthusiasm in our town — and across San Pablo Avenue in Richmond Annex — for making our streets more welcoming to multiple modes of transportation.

The City of El Cerrito has hired a sustainable transportation manager, and our group has seats at the table for an update of its climate plan and development of a local street safety plan, a step toward applying for state and federal funds. Soon construction will begin on protected bike lanes around the El Cerrito Del Norte BART station.

“Every community should have a citizens group whose mission is to understand the potential in the local built landscape for promoting low-carbon multimodal transportation. Local residents who walk and bike every day, alive and alert to their surroundings, will be key to saving the planet,” says my dear husband Steve Price, and people are listening.