Photo by Matt Bennett on Unsplash.

Living with Climate Swings: Heat 101

The Bay Area’s mild weather is a liability in the face of all kinds of growing heat risks, from temperature swings to hotter nights—both in the flatlands and in the hills. The average summer temperature can vary widely, and locals will experience a very different baseline if they live in the notoriously foggy Sunset district of San Francisco or in Solano County’s farmland near Dixon, where 90 degrees is a summertime average. If your town’s summer gradually warms up until most days are around 85 degrees out, you’ll probably not be too uncomfortable at that temperature. But if you live in a place that rarely gets over 70 degrees, a sudden week of 85- degree days can be crippling—or even lethal. “For a senior living in San Francisco that could do a number to your body,” says Angela Yip, an analyst for the City Administrator. But what exactly—geography, surfaces, weather, buildings—helps the heat linger? KneeDeep examines the basic science.

Extremes-in-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

FULL READ

Living with Climate Swings: Heat 101

The Northern California coast is decidedly not associated with hot weather. Yet from wildfires to hot working conditions in warehouses and farm fields, to unique risks for seniors and other vulnerable populations, the Bay Area is distinctly feeling the heat. Though many of us think of ourselves as protected by our moderate Mediterranean climate, in some ways, that climate can actually make us more vulnerable. The Bay Area’s mild-weather infrastructure is a liability in the face of all kinds of growing heat risks, from temperature swings to hotter nights—both in the flatlands and in the hills.

Much of the way any one person is affected by heat depends on the climate their body is accustomed to. Here in the Bay Area, the average summer temperature can vary widely, and locals experience a very different baseline, depending on whether they live in the notoriously foggy Sunset district of San Francisco or in Solano County’s farmland near Dixon, where 90 degrees is a summertime average.

But studies have shown that the health and comfort impacts of temperature vary based on how unusual they are. If your town’s summer gradually warms up until most days are around 85 degrees out, you’ll probably not be too uncomfortable at that temperature. But if you live in a place that rarely gets over 70 degrees, a sudden week of 85-degree days can be crippling—or even lethal.

“For a senior living in San Francisco that could do a number to someone’s body, and really have severe health impacts in some cases,” says Angela Yip, senior communications and legislative analyst for San Francisco’s Office of the City Administrator.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

And, those dangerous temperature swings are one of the main hallmarks of climate change.

“The issue is not so much just that we’re going to be getting hotter, but that we’re also going to be seeing bigger swings,” says Brian Garcia, the National Weather Service’s warning coordination meteorologist for the Bay Area.

More Heat Extremes

Over the next 30 years, the majority of Bay Area counties are projected to see days over 100 degrees more than double, with the greatest impacts projected in Contra Costa, Napa, and Solano counties.

“[Many] parts of the Bay Area benefit from the natural air conditioning of air blowing over the very cold waters of the Pacific Ocean. Once you start moving inland, you’re dealing with ordinary summers and you do experience a lot of heat,” said Ronnen Levinson, head of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s heat island group.

However, these hot days are not expected to ramp up smoothly, as if one turned up the thermostat. Instead, they are expected to be embedded in a bigger trend of increased variability.

“As we march forward, there is a trend of warming climate,” says Garcia. “But within that, we have to be really smart about the averages, because with these bigger swings the basic averages aren’t going to change much.”

Another challenge that more coastal residents face is that, when heat does ramp up, they are often not only less acclimated, but also less prepared—homes often lack air conditioners, fans, swimming pools, and other infrastructure that can help people stay comfortable and healthy.

“People who are unsheltered and are marginally sheltered and those who can’t afford cooling mechanisms are disproportionately impacted,” Garcia says. “In our area the experience is really based on socioeconomic factors: people who can’t afford to have air conditioning in their house, or live in their car, or live or work outside.”

The take-home message is that both individuals and emergency managers should pay particular attention to heat spells (and, in the winter, cold spells) that are out of the ordinary for their particular location and season.

Meteorologist Brian Garcia gives Bay Area weather warnings. Photo: Daniel Dreifuss, Monterey County Weekly.

Feeling the Pressure

More variable temperatures often come in the form of summer heat that is particularly intense or persistent. Then, we start hearing about “heat domes”—which is, according to Garcia, a colloquial term for an area of high atmospheric pressure. Heat domes are not just stifling: they can also impact air quality and make temperatures dangerously hot night.

The high-pressure zone, or heat dome, is a mass of atmosphere—sometimes called an air column, though it can cover vast areas of land—that is literally pushing downwards, toward the ground. This results in a number of interacting effects that help the heat linger. First, as the air gets pushed toward the surface, it condenses and gets hotter, as all gasses do under pressure. An area of heavy, hot air covers the landscape like a thick, invisible blanket.

These high-pressure systems are hot to begin with, but they also trap heat, stopping the surface of the earth from radiating out the heat it absorbs from the sun. They tend to stifle winds, storms, and other disruptions. Clouds are also less likely to form, so they can’t help to block the sun’s heat.

“Typically, under very high pressure, the air is very stable,” Garcia says. “With more pressure of the atmosphere pushing down on the surface of the earth, it keeps things kind of tamped down.”

As the climate heats up, when heat domes form, they are showing a trend of getting more powerful. Their average high pressures are getting higher, and they are lasting longer when they form, according to Garcia.

Catch a Breath

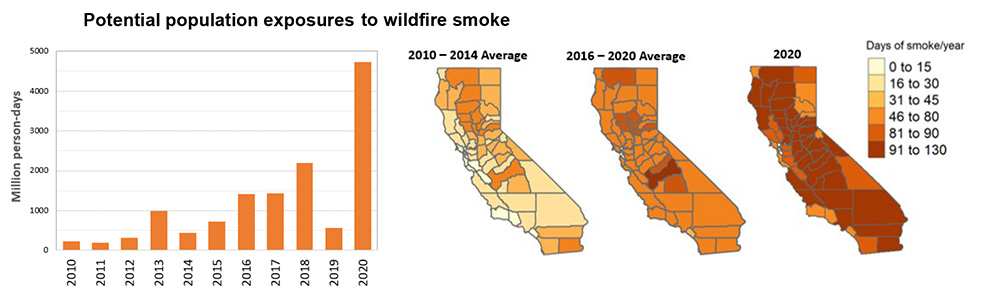

These increasingly powerful heat domes come with an unpleasant side effect: even when there is no wildfire smoke to contend with, hotter temperatures worsen air quality.

There are two main causes of bad air quality. One is particulate matter: car exhaust, wildfire smoke, and so on. Wildfires are most likely to occur when weather is hot and dry, so it’s not uncommon for heatwaves to line up with chokingly smoke-filled air. And the hotter it is, the more likely the particulates are to stick around, trapped by the same high-pressure zones that are turning up the local thermostat.

Source: Indicators of Climate Change in California, Nov. 2022.

Even worse, that trapped car exhaust (along with other types of nitrogen oxide, like industrial emissions) is a key ingredient in smog, the second main cause of low air quality. Technically, this is called “ground-level ozone” and it is generated when heat and sunlight interact with nitrogen oxides and organic compounds. The more nitrogen oxide, heat, and sunlight, the more ozone.

Ozone can lead to breathing difficulty, coughing, and lung problems. And it’s most likely to occur in urban areas, where the cars are concentrated and vast swathes of pavement and buildings serve to further bump up the temperature—in other words, where the ingredients for this life-sized chemistry experiment are the most concentrated.

Air quality and air temperature interact in a complicated dance, leading to challenging decisions. A recent red-flag weather day in Sonoma County found various public buildings, including 11 of the county’s 15 public libraries, closing down when drift smoke from wildfires made indoor air quality unacceptable. Patrons, who often include unhoused people, had to go find other—hopefully air conditioned—spaces to escape the heat.

Tighten Your Belt

Heat domes can also create heat risks in surprising places. We often assume that mountains are cooler than lowlands, but high pressure systems can create the opposite effect.

High pressure zones can create thermal belts: these are elevation bands where the air stays warm as the weather system presses over the region like a lid, holding the warm air in. When this lid sits all the way down at ground level, we get no overnight cooling; everywhere stays stiflingly hot. But when the high pressure zone is sitting a bit higher, then homes at lower elevations—say, at the bottom of a valley, or on the edge of the Bay—will experience overnight cooling, whereas those higher in the hills will not.

“Overnight, the earth likes to radiate all that heat that it sucked in [during the day],” says Garcia. “But what happens is there’s a zone where that rising heat no longer rises.”

A thermal belt generated consternation in the Berkeley hills during last year’s September heat wave, when Bay Area temperatures soared well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. While the temperature down in the flatlands dropped to the mid-60s by 11:30 p.m., it was still a roasting 92 degrees up in the hills. By the following daybreak, the hillside temperatures were still around 87 degrees—offering little relief as residents geared up for another scorching day.

“So now you have heat health risks from that overnight cooling not occurring to the degree that you would normally be used to in some of the populated areas,” Garcia says.

Fire danger is also significantly higher in thermal belt zones, Garcia says. “We get concerned about it in the fire world, because a fire’s burning may remain very active above the thermal belt overnight.”

The Importance of Chilling Out

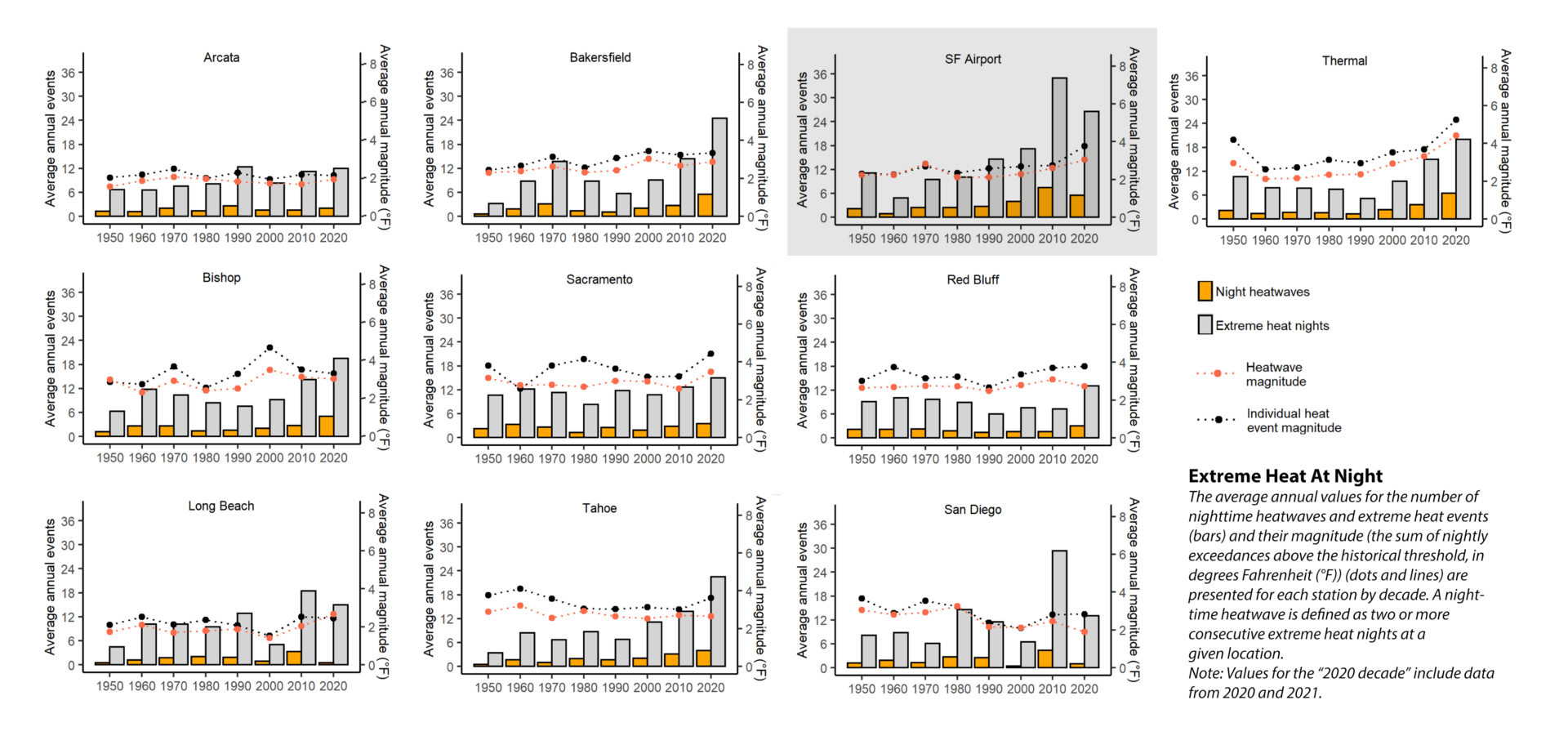

Hotter nights are not just a problem in the mountains. Overall, average nighttime temperatures are climbing much faster than daytime temperatures—and that’s not just bad for your sleep, it’s bad for human health overall.

“Here in the coastal West, the daytime highs might be only a little bit warmer in general, which isn’t a big deal—if instead of being 85 in East Bay, it’s 90, we can deal with that,” says Garcia. “But, we need the opportunity for the body to then release some of that heat with the overnight cool.”

Source: Indicators of Climate Change in California, Nov. 2022.

Part of the reason for the warmer nights is the increase in strength of high pressure zones, Garcia says. Another is increasingly warm sea surface temperatures—a lot of coastal cooling is the result of winds blowing across the comparatively cold surface of the seas, and carrying that chill onto land. But as seas warm, that effect lessens.

Along the coast, a cool evening can be a blissful relief after a long, hot day. Even when the fog doesn’t roll in—which it frequently does—a refreshing wind almost always kicks up, dropping the temperature and making one ready to grab a blanket or two by bedtime.

Yet as discussed above, some nights are different: the heat doesn’t fade. Once again, the problem is worse in urban areas.

“A lot of the biggest heat health impacts are from people sleeping indoors in buildings that have been heating up all day,” says Alex Morrison, GIS analyst with the San Francisco resilience and capital planning office, who co-led the development of the city’s recently-released Heat and Air Quality Resilience Plan.

“If heat isn’t able to effectively get out of the building when night comes, it doesn’t allow people’s bodies to have that break. [If there are] multiple days of that, you’ll start to see the health impacts,” Morrison adds.

Photo: OES.

While sometimes a lack of cooling can be a feature of the heat wave, as with heat domes or thermal belts, it can also be a function of building design and an equity issue. Things like poor air circulation, single-paned windows, substandard insulation, and a lack of air conditioning can all lead to heat retention.

Overall, this is a problem for many homes throughout the Bay Area; the region has the lowest number of air conditioners in the US, according to a 2021 survey. While a national average of 92% of homes have air conditioning, only 45% do in the San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward metro area.

“Because [homes here] generally don’t have AC, we don’t have the capacity to cool ourselves easily when we have extended periods of heat,” Garcia says.

City Surfaces and Interiors

In cities, heat impacts are compounded by a phenomenon known as urban heat islands.

“Traditionally, the causes of elevated air temperatures in cities stem from having a lot of dark dry surfaces where, in the past, you used to have wet vegetation. And there’s also heat that’s generated from human sources, like our vehicles or the exhaust from our air conditioners. And sometimes you used to have more shade than you do today,” Levinson says.

Photo by Saketh Garuda on Unsplash.

In a typical urban environment in the US, the temperature will generally be 1 to 7 degrees higher than in the surrounding area, where vegetated landscapes dominate, according to the EPA. Worldwide, that difference can sometimes be as great as 59 degrees Fahrenheit.

But, Levinson adds, there are steps people can take to turn down heat. At the individual property level, re-painting and re-roofing buildings with light-colored or specially designed refractive materials can lower “uncomfortably hot” interior hours by up to 41%, with the biggest improvement seen when air conditioning is not available. Additional cooling can be gained by shading the ground outside the buildings: with trees, arbors, awnings, shade sails, or even freestanding yard umbrellas. And if enough property owners in a neighborhood make this change, the local heat island effect can be reduced as well, says Levinson.

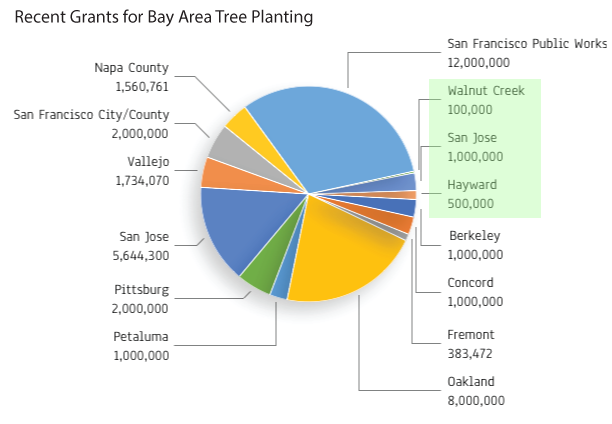

Trees are one of the most desirable forms of shade—anyone who has ever stepped from a baking sidewalk into a park shaded with green trees knows the difference that living shade can make, even if the landscaping is drought tolerant. Living vegetation not only has a greater cooling effect, but also improves air quality and provides aesthetic and recreational opportunities as well. Studies have even shown that trees are associated with reduced crime and increased investments and economic opportunities. In light of these facts, it’s unsurprising that myriad tree planting programs are taking place throughout the Bay Area.

2023 US Forest Service Urban and Community Forestry Program grants in the Bay Area (green box is for maintenance and resilience projects). A total of $1 billion was awarded nationwide.

In September, the US Forest Service’s Urban and Community Forestry Program awarded nearly $38 million to 12 Bay Area cities and counties for tree planting, as well as smaller awards for maintenance. The largest awards went toward tree planting in San Francisco ($14 million) and Oakland ($8 million).

“Our goal [is] not only drawing down carbon for future mitigation of climate change, but also increasing tree canopy, improving air quality, reducing urban heat effect, and providing a variety of biodiversity habitat spaces,” says Hoi-Fei Mok, Sustainability Manager for San Leandro, who is overseeing a CalFire grant to plant 1,000 trees, nearly 650 of which have already been installed—an effort that spanned seven planting events and over 1,400 volunteer hours, Mok says.

“The project was very much in collaboration with community groups. We had a lot of volunteers coming out to our tree plantings over the year—it was very intense,” Mok adds.

Efforts to adapt to and mitigate heat efforts range beyond urban greening, however. This month San Francisco’s Department of Emergency Management awarded 90 community-based organizations air filters and air conditioners.

“We are trying to be proactive before we reach the projected reality of San Francisco having dozens of days that are over 85 degrees,” says Morrison. “Because once it’s above 85 degrees, you start to see emergency department visits go up, you start to see health impacts spike in the community.”

Fighting for Fairness

Ultimately, the human experience of heat in the Bay Area largely boils down to an equity issue.

“Generally speaking, there are strong equity aspects to extreme heat,” says Max Wei, sustainable energy systems program manager at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

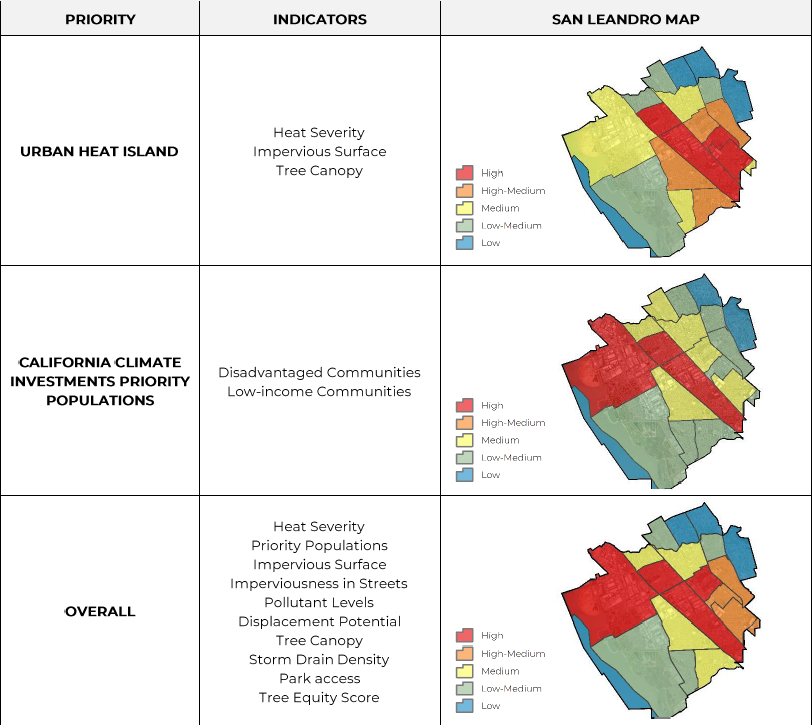

While cities are hotter than rural areas, some neighborhoods get hotter than others during heat waves, and may also have significantly longer “heat seasons”.

“Disadvantaged areas tend to be hot and also have a high pollution burden,” says Wei. “And the buildings that people in these areas tend to live in tend to be older. Also, in general, people tend to have a higher rate of underlying health conditions.”

Various vulnerabilities pinpoint which neighborhoods needed more shade or more trees the most. Chart: City of San Leandro.

Because lower-income areas often lack official weather stations, extreme heat warnings could further fail the communities that are most at risk, studies have found.

Challenges rise as a neighborhood’s lack of resources stacks up: from trees, parks, and swimming pools to air conditioners and ceiling fans. If fewer residents have cars, or gas money, they can’t drive somewhere to beat the heat. Where most buildings are rentals, or where owners are low-income, maintenance and upgrades to landscaping and infrastructure are less likely.

“In a place like Phoenix, they are better prepared because they are used to having heat waves. But in a place like Oakland or maybe Santa Rosa there is less awareness,” Wei says.

“We are very interested in improving resilience,” adds Wei. “We want to provide higher margins of safety.”

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Special Thanks for Climate Swings story

Background Science: Bruce Riordan, UC Berkeley

Graphics Support: Darren Campeau

Banner Image: Photo by Ronan Furuta on Unsplash.