Return of a Lost Lake

This winter’s 31 atmospheric rivers proved too much for the man-made system of dams and diversions designed to siphon off an ancient lake’s water for agriculture. On the heels of the worst drought in 1,200 years, Tulare Lake, at the southern end of California’s San Joaquin Valley, filled and filled again in the heavy rains and runoff from its lower watershed, inundating over 100,000 acres of farmland, cities, and homes in the drought-dry lake bed between Fresno and Bakersfield. As the Sierra snowpack melts over the next few months, the lake could spread, prompting water managers and locals to reconsider the future of this lake, long thought “dead.” What would it look like to let the lake recover? One thing is clear: the lake wants to be here.

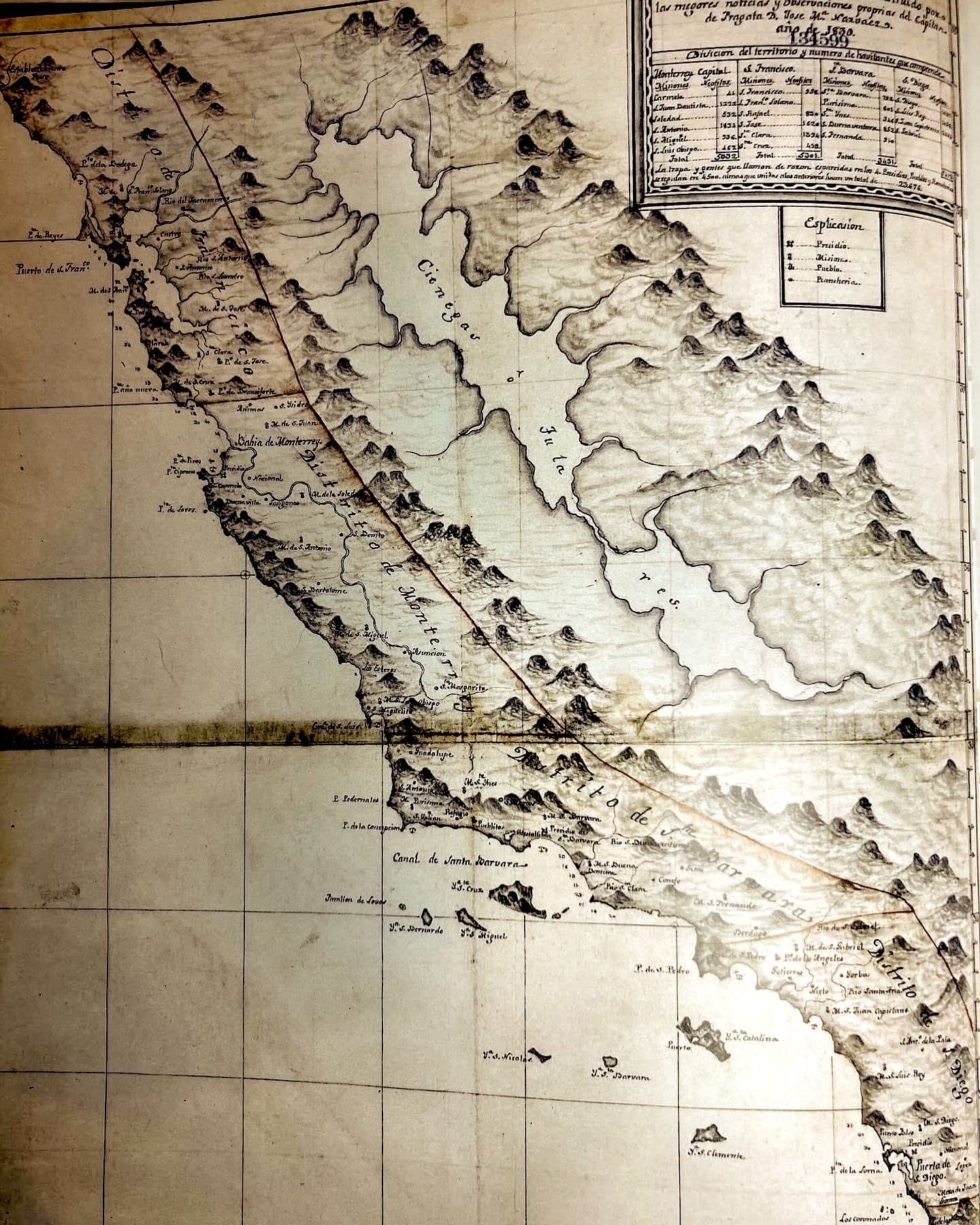

Historic map recorded by early Spanish surveyors of Tulare Lake’s extent. Map courtesy: Tachi-Yokuts.

Extremes-in-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

FULL READ

Return of a Lost Lake

This winter’s 31 atmospheric rivers proved too much for the man-made system of dams and diversions designed to siphon off an ancient lake’s water for agriculture. On the heels of the worst drought in 1,200 years, Tulare Lake, at the southern end of California’s San Joaquin Valley, filled and filled again in the heavy rains and runoff from its lower watershed, inundating over 100,000 acres of farmland, cities, and homes in the drought-dry lake bed between Fresno and Bakersfield. As the Sierra snowpack melts over the next few months, the lake could spread to 130,000 acres, according to the California Department of Water Resources, prompting water managers and locals to reconsider the future of this lake, long thought “dead.”

The reemergence of the lake — christened “Los Tules” by early Spanish explorers for the plentiful rushes and reeds of its then-extensive marshes — is either a spiritual experience or a disaster, depending on your relationship to the land. But one thing is clear: the lake wants to be here. The lake’s bottom is made up of a highly impermeable layer of Corcoran clay, after which the city of Corcoran — built in the lake’s bed — was named. When dams and pipes were overwhelmed this winter, the clay was happy to hold onto all of the runoff from the four rivers — the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern — that feed it. The last time the lake was this full — in 1983 — it stayed around for two years.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A seven-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Part 6: Infrastructure

Part 7: Aftermath

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

The Tachi-Yokut Tribe derived its name from the mud hen, or American coot, a once permanent resident of the lake. Photo: Pamela Rose Hawken

Although the flooded lake is viewed by many farmers as an inconvenience that could affect crop production and food prices this year, the lake — before it began to be cultivated by early European settlers and later by industrial agriculture — was once much larger. It stretched across 200,000 acres in wet years, making it the largest freshwater body west of the Great Lakes. The most extensive complex of freshwater wetlands west of the Mississippi surrounded the lake, and wildlife flourished here. Herds of tule elk, grizzly bears, and black bears wandered among the adjacent oak forests and brought their young to the lakeshore to feed. Indigenous people trapped or hunted birds from the plentiful waterfowl gathering at the lake’s edges, drawn to the area because of its location on the Pacific Flyway.

Pumping History Away

Beginning in the mid-1850s, Europeans began colonizing the area, farming the lake and grazing cattle in its bed. In addition to transforming this ecosystem, they violently displaced Indigenous people while the U.S. government nullified longstanding treaties. Tens of thousands died.

European colonization and destruction was followed by large-scale industrial agriculture that diverted freshwater flows from the rivers feeding the lake and pumped groundwater from beneath it to grow thirsty crops like cotton. Over the years, the aggressive pumping became unsustainable, and after several decades of drought, interrupted by a few rare wet winters, the Tulare Basin was designated as “critically overdrafted” by the state Department of Water Resources. The basin is one of 21 so designated out of 515 groundwater basins in the state.

As a result of overpumping, the basin has subsided, or dropped, as much as 20 feet in some places, says Steve Haze, Executive Director of the Tulare Basin Watershed Network, who has lived on the periphery of the Tulare Basin his whole life and has watched as unsustainable land use practices continued. Water-guzzling crops like cotton, alfalfa, corn, and tomatoes are still grown in the lake bed despite the over-pumping and subsidence. Driving around the lake’s flooded perimeter recently, Haze looked down onto the lake bed from behind levees and saw pistachio orchards and solar farms that had been installed in the recent past, prior to the flood. He also saw “lots of roads blocked, some roads gone, parts of cars stuck in the mud.”

Young nut trees, planted earlier in the lake bed, after the winter rains of 2023. Photo: Ken James, Department of Water Resources.

The whiplash weather brought on by climate change has pushed locals and government officials to come together to figure out long-term solutions to the unprecedented combination of drought, flood, and groundwater overdraft. California’s groundwater basins were not regulated until 2014, when the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act was finally passed. Eight years later, as the brutal drought continued, the state took more action to try to replenish shrinking groundwater resources through a new effort managed by the state Department of Conservation, the Multibenefit Land Repurposing Program. Program managers hope to recharge groundwater by encouraging regions, through block grants, to fallow some of their farmland: to give the land a rest or find new, more sustainable uses for it. In 2022, the Tulare Basin region was awarded two $10 million grants from the program. While planning is still underway for those repurposing projects, the goal of the program is to give the groundwater table a chance to recover while providing new jobs and economic benefits to farmers and other community members. Repurposing can involve restoring the land to wildlife habitat including wetlands, creating parks and other “green infrastructure,” or other such passive uses.

“We’re all having to come to the table, and grudgingly put on our thinking caps to think outside the envelope,” says Haze. “Better late than never, though, with climate change. We’re in the driest period in 1,200 years but the difference is we have 40 million people in this state now.”

Historic map of Tulare Lake in 1873. Map: Wikimedia Commons.

Mirage or Glimmers of Return?

Haze could foresee a Tulare Basin that looks more like the Delta, with a patchwork of habitat and land uses, to start with. But his ultimate vision for the basin is to recreate a “string of emeralds,” a chain of wetlands leading into and around the lake. A realist, he knows restoring the entire lake to what it was may be unlikely: “Even if you’re just looking at [restoring] 10% of the historic lake — that would be an achievement in itself. That’s what the string of emeralds would be, taking the historic hydrology and building off of that and putting back the green infrastructure.” He’s surprised and encouraged by the state dedicating $90 million to its new land repurposing program, which gives him hope for recovering lost ecosystems like the Tulare Lake basin. “Just because we’ve reached the tipping point, doesn’t mean it can’t go back the other way.”

The Tachi Yokuts’ cultural director Shana Powers, says the first and only time she saw the lake flooded as a child, she was awestruck: “Seeing something like that in an area where you don’t think of water and knowing that that is what it is supposed to look like—it changed the way I viewed the entire world.”

Powers, too, would love to see the lake restored. Key to any restoration, she says, is making sure the lake can once again both flood and flow. Although the Tulare Basin is often spoken of as being a “closed basin,” it is actually an open basin, she explains. “Prior to the diversions on the Kings and Kern rivers, the lake flowed north about 60% of the time,” she says. “Even in extreme drought, the lake still overflowed into the Kings River 40% of the time.” So allowing flooding—and restoring flows by removing some dams — would help recharge groundwater over time, and also help dilute the salts and other byproducts of farming now lacing the lake bed. “If you do not manage your soils properly,” Powers says, “you cannot recharge groundwater. And when you’re constantly killing the land, we can’t recharge the water either.”

Powers adds that the tribe has always understood the cycle of drought and flood in this state of climate extremes, even changing their diet in lean times instead of trying to control nature. She says restoring the lake — instead of building new dams — could save taxpayers billions of dollars. She also says that bringing back the lake would restore a sense of place and identity to the Tachi-Yokut Tribe as well as much-needed habitat for wildlife. And it would help build resilience to upcoming climate challenges, Powers says. “If we are looking at temperature increases with climate change, there will be more drought and more flood because the water can’t stay in the mountains as snow. There will be a rapid release and we do not have the infrastructure to capture it. Tulare Lake is made to hold water.”

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Reporting supported by Pulitzer Center, Connected Coastlines.