30 East Bay Partners Gel on Adaptation Path

On an overcast June afternoon at Bay Farm Island’s Veterans Court, Danielle Mieler explains that if it weren’t for low tide, water might be at her feet.

Veterans Court — a shoreline pathway frequented by runners, bikers and fishers — runs along the edge of the San Leandro channel and, along with the rest of the island off the East Bay shore, is vulnerable to future flooding.

“We saw this potential for a tragedy of the commons,” says Mieler, the city of Alameda’s Sustainability and Resilience Manager.

Worried sea level rise will only make matters worse, Mieler co-created the San Leandro Bay/Oakland-Alameda Estuary Adaptation Working Group a year ago and it now has 30+ partners. The group’s aim is a collaborative action plan to accelerate sea level rise adaptation, protect and restore water quality and habitat, and promote community resilience.

Mieler was inspired by the San Francisco Estuary Institute’s Adaptation Atlas, which divides the San Francisco Bay shoreline into 30 distinct geographical areas that share physical characteristics. These areas, called operational landscape units (OLUs), don’t adhere to the jurisdictional boundaries of cities and counties, but rather to the boundaries of natural processes like tides, waves and sediment movement. Mieler described the OLU framework as a biological blueprint for sea level rise adaptation planning. She felt like the atlas was languishing on a shelf, though, so she took matters into her own hands and created the working group in July 2021 with her colleague, Gail Payne, Alameda’s transportation coordinator.

“We wanted to really expedite getting to implementation,” Mieler said. “This really does need to be coordinated across jurisdictions and it’s bigger than just a city scale issue. Even within cities, there’s many different stakeholders.”

The one-year-old working group is organized around the San Leandro OLU, a highly urbanized mixed-use area with very little open space that stretches from the Bay Bridge to Oyster Bay Regional Shoreline.

Mieler emphasized the importance of cross-jurisdictional collaboration, noting that the shoreline connects an array of different communities and ecosystems that must work together to address sea level rise.

”I just think we need to come together, have a common voice and be able to advocate for what we need,” Mieler said.

The group’s partners include the cities of Oakland and Alameda, Caltrans, the East Bay Regional Parks District, and the Port of Oakland. Several community partners are also participating in planning, including the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project, Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, the Lisjan Nation, Community Action for a Sustainable Alameda, and the East Oakland Collective.

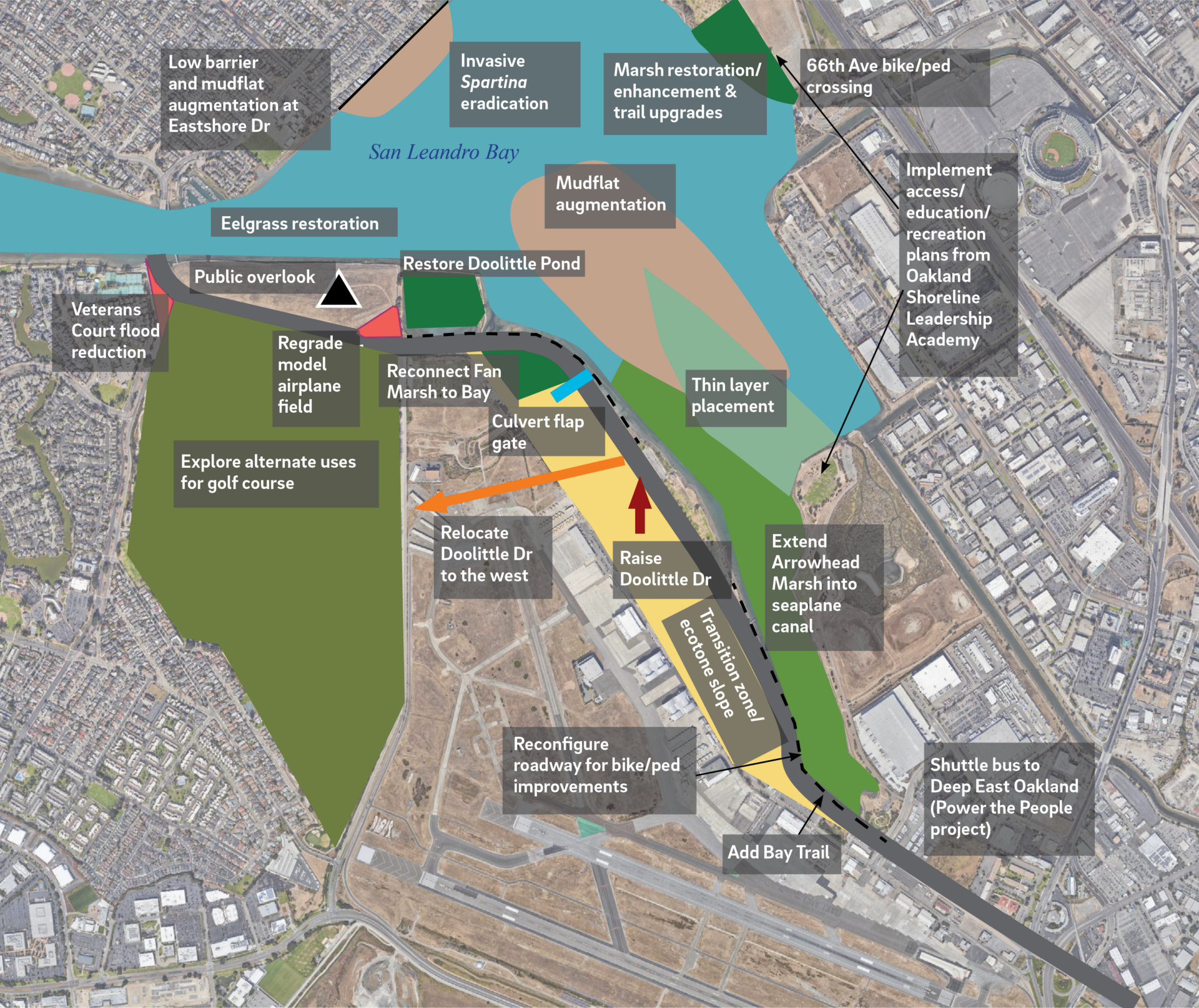

Using some of the Estuary Institute’s adaptation pathway tools, partners are already exploring options. Major assets vulnerable to sea level rise are located within the San Leandro OLU, including the Port of Oakland, Oakland International Airport, the MLK Shoreline and major transportation corridors like interstate 880 and Doolittle Drive. Several stakeholders have already conducted vulnerability assessments on their own, and the Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s Adapting to Rising Tides Program completed three studies within the San Leandro OLU. The working group will coordinate and implement the plans of impacted stakeholders to achieve a unified outcome.

Protecting Veterans Court

Veterans Court, a dead-end cul-de-sac connecting residential areas to shoreline trails and a fishing pier on Bay Farm Island, is already experiencing flooding. The flooding also plagues Doolittle Drive and adjacent neighborhoods. The island’s shoreline has the highest wave heights in the San Leandro OLU and among the highest in San Francisco Bay, making it vulnerable to wave erosion. The existing coastal defenses and low-lying urban edges are no match for storm surges and rising groundwater, which often lead to overtopping.

The City of Alameda is considering replacing the court’s seawall with a living levee, which is a vegetated embankment that slopes gently downward and can support marsh in the tidal zone. The group is also considering planting submerged vegetation such as eelgrass offshore to slow currents and sequester carbon.

Barbara Lee describes $$ and community projects for the shoreline. Photo: Maurice Ramirez.

At a June 3 press conference at Veterans Court, Congresswoman Barbara Lee announced an earmark of $1.5 million of federal funds to strengthen coastal resiliency and adapt the Veterans Court area to the immediate threat of flooding.

Alameda mayor Marilyn Ezzy Ashcraft echoed support.

“By mid-century the profound impacts of sea level rise will be multiplied by more frequent and more powerful storms, which is why we are so grateful to Congresswoman Lee for securing critical funding for the city of Alameda,” Ashcraft said. “Right where we are standing here today, your feet will get wet and then some.” Mayor Ashcraft said the city’s goal is to protect homes and businesses on Bay Farm Island from inundation.

“Sea level rise knows no jurisdictional boundaries,” Ashcraft said.

Getting Organized

The new work group is still working out the best organizational structure, Mieler said.

In support of its efforts, the San Francisco Estuary Partnership, a member of the working group, set aside $300,000 of funds that will allow the group to pay its community partners for their participation.

“You have to have that locally-driven process because people are tied to place,” said Caitlin Sweeney, director of the Partnership.

Though Sweeney wants to help, she also doesn’t want the partnership, which is a federal program with its own regulatory constraints, to delay on-the-ground progress on the Oakland and Alameda shoreline.

The Oakland Estuary adds additional flood risk to the cities on both sides via sea level rise. Photo: Maurice Ramirez.

For now, agencies such as SFEP can lend assistance in helping OLU partners decide on a governance structure, in addition to providing sea level rise projections and funding.

Keta Price, a community partner who is the former director of urban and regional planning with the East Oakland Collective and now runs Hood Planning Consulting, is engaged in the work group’s efforts to involve Black and Brown communities. Price says efforts to improve infrastructure along the shoreline should go hand-in-hand with efforts to improve social justice and community engagement.

“The goal is to get more people in the community into planning organically, to get them to understand it and to be a part of the process more authentically,” Price said. “I am really in these spaces for racial and economic justice.”

Price used to frequent the Oakland shoreline in her youth for family reunions and jet skiing, though she doesn’t know anyone that goes to the shoreline anymore. She said she’d like to see the shoreline be more accessible, not only physically, but culturally.

In its 2019 community plan, the East Oakland Neighborhoods Initiative called for a San Leandro Creek greenway linking the Elmhurst neighborhood to the shoreline, and a bicycle and pedestrian bridge over I-880. Additionally, the Collective is partnering with Oakland’s Department of Transportation on a project analyzing the feasibility of a zero-emissions bus route connecting East Oakland to the shoreline.

The OLU working group recently received a grant from Caltrans to develop adaptation plans for the northern shoreline near the Posey Webster tubes and the Oakland estuary along Jack London square. Mieler says the grant includes funds to ensure that community partners like Price are active participants in the development of these projects.

Click to see enlarged slideshow.

Big Property, Big Risk

The biggest property owner in the working group, the Port of Oakland, manages important infrastructure along the Oakland shoreline, where decades of industrial activity have significantly altered the bayshore’s physical characteristics. The Port’s 2019 vulnerability assessment found that several areas were threatened by sea level rise, especially Doolittle Drive.

Matt Davis, the Port’s Director of Governmental Affairs, said the port has been conducting a vulnerability analysis on the levee that surrounds the airport’s commercial runway, which is adjacent to the bay. He said the port is expanding the scope of its analysis to try and understand how planning and projections will affect neighbors — staying true to the working group’s emphasis on interconnectivity of communities and ecosystems.

“Mother nature doesn’t respect any geographical or jurisdictional boundaries,” Davis said. “The water is going to flow where it finds the most vulnerable area.”

Studies conducted by BCDC, a working group member, identified nature-based solutions for the shoreline along the port, such as the addition of coarse beaches and restoration of shallow subtidal habitats. These dovetail with habitat projects suggested by the OLUs around the port. Additionally, Caltrans is seeking funding to study Doolittle Drive’s vulnerability to sea level rise, and the East Bay Regional Parks District included the road as a priority location in its district-wide risk assessment.

What’s Next?

Following guidance from San Francisco Estuary Institute, next steps for the working group will be to create a clear governance structure and decision-making process to ensure the voices of all stakeholders and impacted communities are heard.

“I think the biggest concern is how do we ensure our work really reflects the needs of all parties and lifts up the voices of the community?” Mieler says.

Price says that thus far, she thinks that Black and Brown communities are being adequately engaged in adaptation efforts within the working group.

“I feel like we’re on a good track,” Price said. “As long as we continue to be transparent and are willing to be vulnerable with each other, then I feel like it’s going the right way.”

Planning for sea level rise adaptation with multiple stakeholders across a vast, complex shoreline is an impressive feat, but for now, the working group is taking it one step at a time.

“We have some really gnarly problems in this area that will require out-of-the-box thinking, new forms of governance, deep collaboration, a lot of foresight and buy-in of the community,” says Mieler. “We’re just beginning.”