100+ Easements for One Flood Wall?

“I fear delays will put us at risk. Time is not on our side.”

Gina Solomon bought her house in part for what lies just outside the back door. The property in northern San Rafael includes a small private dock extending out over marshland into Gallinas Creek, a winding tidal slough that meets San Pablo Bay about a mile and a half away. “We canoe and kayak and paddle board, so we like to be out on that creek,” Solomon says. She also cherishes the unspoiled view of the surrounding coastal plain, with 1,600-foot Mount Burdell off in the distance.

There’s a lot to like about Santa Venetia: the closeness to nature, the quiet, the modest ranch homes with an artistic flair. But for Solomon and many of her neighbors, Santa Venetia’s greatest asset is also its greatest threat. All that protects her home and hundreds of others from Gallinas Creek waters that rise and fall twice a day – and by extension the whole of San Pablo Bay – is a short, timber-reinforced earthen berm constructed in 1983. Already well past its useful life and failing in numerous spots, the berm is also increasingly threatened by storm surge and sea level rise.

But replacing it won’t be easy, with funding shortfalls, property-access issues, and environmental concerns all delaying efforts to design and build a new wall over the past decade. And while Santa Venetia is unique, its current situation is emblematic of what may soon face many others up and down the San Francisco Bay shoreline, where the pleasures of waterfront living meet the reality of climate change and the cold calculations of the balance sheet.

Familiar Flood Risk Gains New Urgency

Flood risk is nothing new to Santa Venetia. The neighborhood was constructed in the 1950s on a former mudflat, and due to subsidence now sits entirely at or below sea level. It would become a bathtub every winter if not for the 14 pumps at five different stations that lift rainwater back out and over the wall.

San Rafael’s Canal neighborhood, built on fill along the banks of San Rafael Creek near downtown, faces a similar predicament. It requires pumps to stay dry each winter, and a new levee is in the works to ward off rising tides. Sea level rise is also coming fast for low-lying areas of nearby Corte Madera and Marin City and, on the county’s ocean coast, Stinson Beach. In March 2024, Marin supervisors committed $500,000 toward developing a unified approach for responding to sea level rise countywide.

Santa Venetia’s Gallinas Creek last spilled its banks during the record-setting winter of 1983, inundating streets and 160 homes with water up to five feet deep. The current berm, constructed shortly thereafter, has kept Santa Venetia safe ever since. But erosion, subsidence, and gophers have severely compromised its strength, just as climate change has made it more likely that floodwaters will overtop the berm. All it will take to flood the neighborhood again is one significant failure on the berm or one poorly timed convergence of high tide, storm surge, and rainfall.

Solomon recognizes the urgency. “The community of Santa Venetia is at very high risk,” she says, “and I do fear that the delays getting the new wall in place will put us at risk of flood. It could happen any winter, really, and time is not on our side.”

There are numerous reasons it’s already taken so long. After years of work, the County of Marin in 2019 received nearly $3 million from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for the design and construction of a new flood wall between the creek and the community. But it had to go back to the drawing board after costs escalated and a 2021 tax measure to fund $1 million of the project’s $6 million price tag failed among Santa Venetia residents by just three votes. Many waterfront residents also refused to grant easements or access to their yard for construction of a new wall.

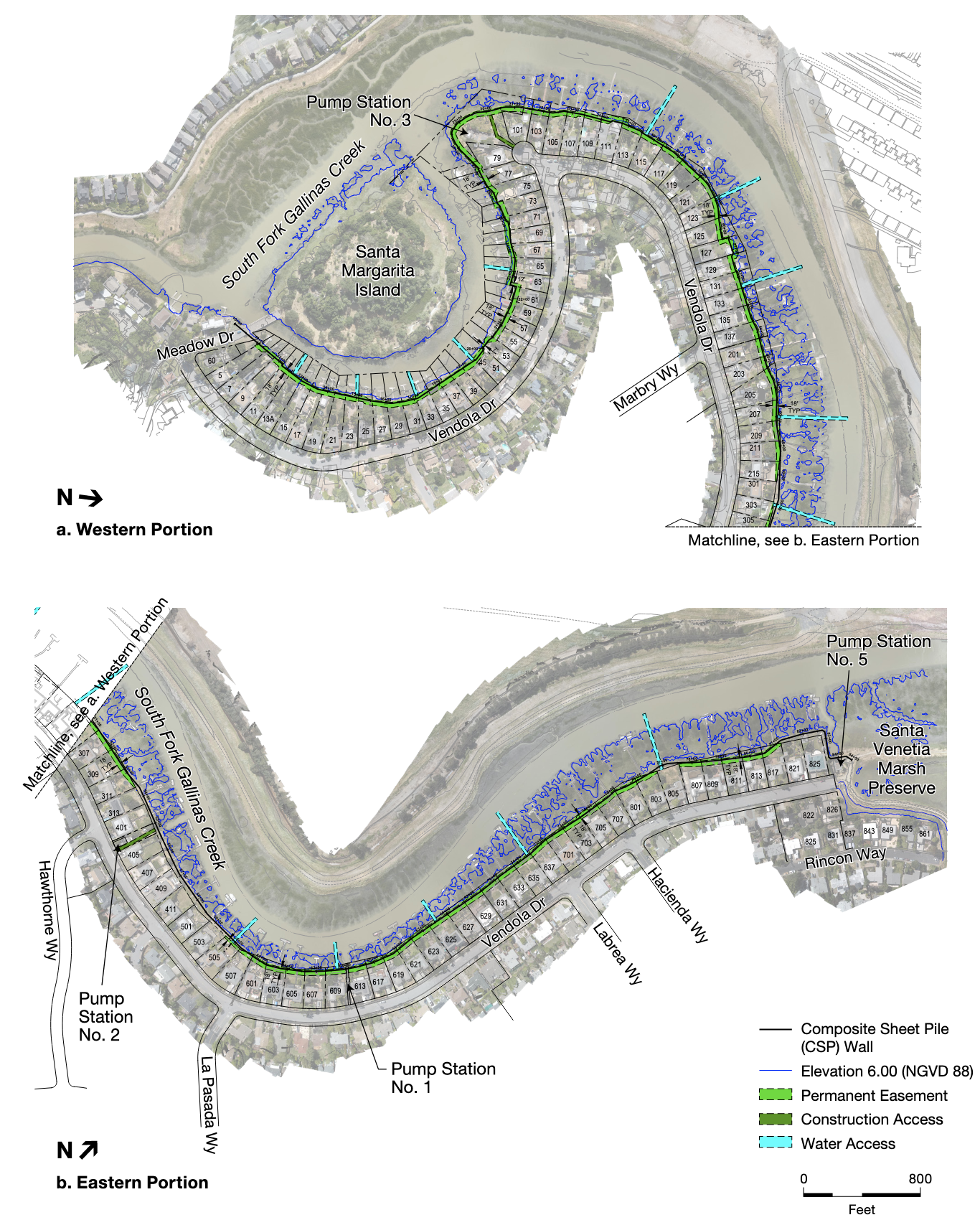

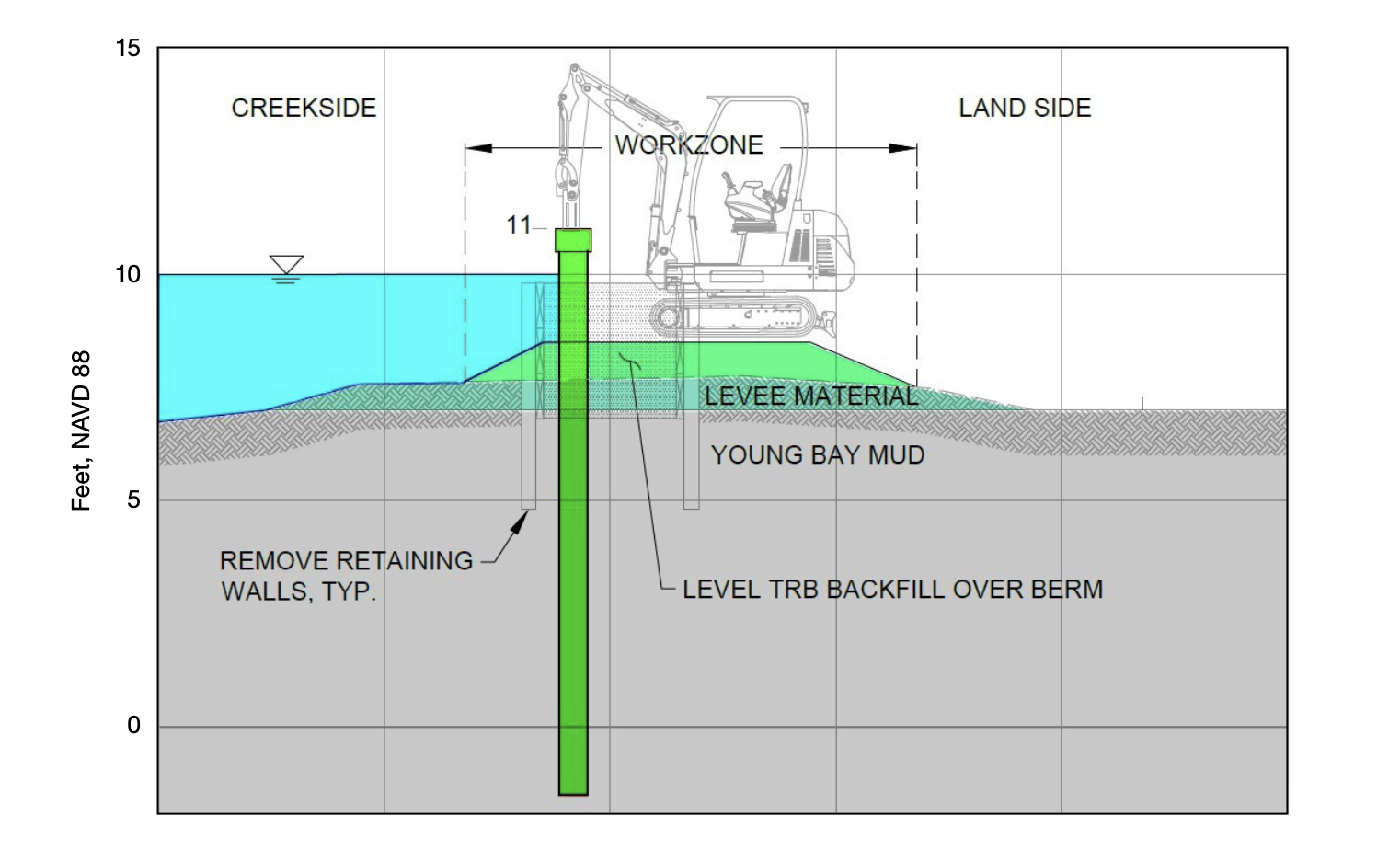

The county hired another set of firms in 2022 to draw up a new plan for replacing the existing berm with a 1.5-mile composite sheet pile flood wall (fiber-reinforced plastic sheets with interlocking edges). But the work would be performed largely by boat to reduce impacts on private property, raising questions over potential impacts to endangered longfin smelt. An ensuing California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) report should be wrapped up this summer.

Photo: Nate Seltenrich

Needed Upgrades Require 100 Signatures

The new design will cost more than $15 million to build. The county can’t afford it without another grant from FEMA, but in order to receive one, it’ll still have to convince every homeowner along the length of the proposed wall to agree to sell the county a waterfront easement, something Tracy Clay, flood control division manager for the Marin County Department of Public Works, worries it won’t easily achieve.

“This is a huge challenge,” she says. “We have 111 properties, and we have to get all of them or we cannot apply to FEMA. FEMA will provide funding for voluntary acquisitions. They will not provide funding for eminent domain acquisition. So if we had to go through eminent domain acquisition, that would have to be some other source [of funding].”

Solomon says she’s among the relatively few residents who have already agreed to the easement. “We signed on and approved the easement early on,” she says. “We’re not thrilled about the fact that the sheet pile will probably interfere with our view. But that wasn’t reason enough for us to stand in the way of this project.” Other residents, however, have expressed concerns about losing water access, privacy, control over their property, and trees and structures currently situated atop the timber-reinforced berm, explains Greg Fox, chairman of the flood zone advisory board. “Those homeowners are rightly concerned about giving up an easement, and what the design of the levee is going to be like, and what the impact on their property is going to be.”

County Supervisor Mary Sackett, whose district includes Santa Venetia, said the county takes some responsibility for its failure to obtain many voluntary easement agreements to date. “The easement language as initially drafted was really broad and some people didn’t want to sign it voluntarily,” she says. “So then we went back to make it more narrow language. The easement is just to construct this wall and to do annual maintenance, and if we ever need to replace it again, we have that right.”

Fundraising “a Hard Sell”

But easements aren’t the only issue still standing in the way of a new wall. A FEMA grant will also require a local funding match to the tune of $3.8 million, which the county also doesn’t have. Residents could vote to tax themselves to cover at least part of this cost – though if such a measure were to fail it could put the project in jeopardy, just as it did in 2021.

Local educational signage and schematic for how to build the flood wall. Photo: Nate Seltenrich; Schematic: Marin County Flood Control District

“I think it’s gonna be a hard sell,” says creekside resident Jami Ellermann. But if the timing is right and some past mistakes are avoided, she says, then the outcome on a second tax measure – even one much larger in size – could be different.

Residents already pay into the flood zone budget via a 1% ad valorem property tax, and Fox says he’s worried about the prospect of additional tax posing a financial burden for some residents. Despite its waterfront setting, Santa Venetia is not a wealthy neighborhood by Marin standards. Roughly 45% of residents are over 65 years old, compared with about one-third countywide. And the median income is $119,600 – about 16% lower than countywide.

“My highest concern is, honestly, not even about the easements or the property rights. I think we’ll get that sorted,” Fox says. “But I am concerned about raising the money locally without putting people on fixed incomes into hardship. So we’ll need to come up with a structure for that, and possibly other sources of funding.”

Meanwhile, the county is spending roughly $450,000 per year just to patch holes in the existing berm, and potentially more for emergency repairs and sandbag deployments during storms. And the fact of the matter is that the current value of property behind the failing berm exceeds any potential costs to replace it by orders of magnitude.

“A little back-of-the envelope … there’s probably something short of a billion dollars of real estate in the floodplain,” Fox says. “It’s a great community. It’s very peaceful and beautiful. it’s worth saving, and I’m convinced we’re going to do that.”